year

stringdate 1959-01-01 00:00:00

2025-01-01 00:00:00

⌀ | tier

stringclasses 5

values | problem_label

stringclasses 226

values | problem_type

stringclasses 16

values | exam

stringclasses 28

values | problem

stringlengths 0

10.4k

| solution

stringlengths 0

24.1k

⌀ | metadata

dict |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

2024

|

T1

|

5

| null |

USAMO

|

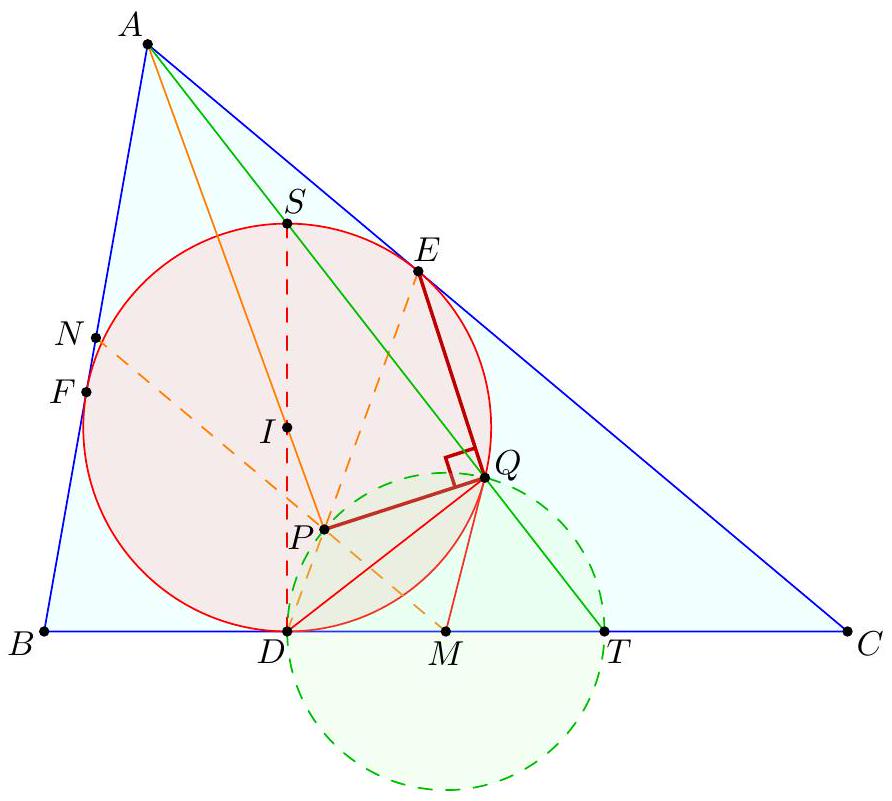

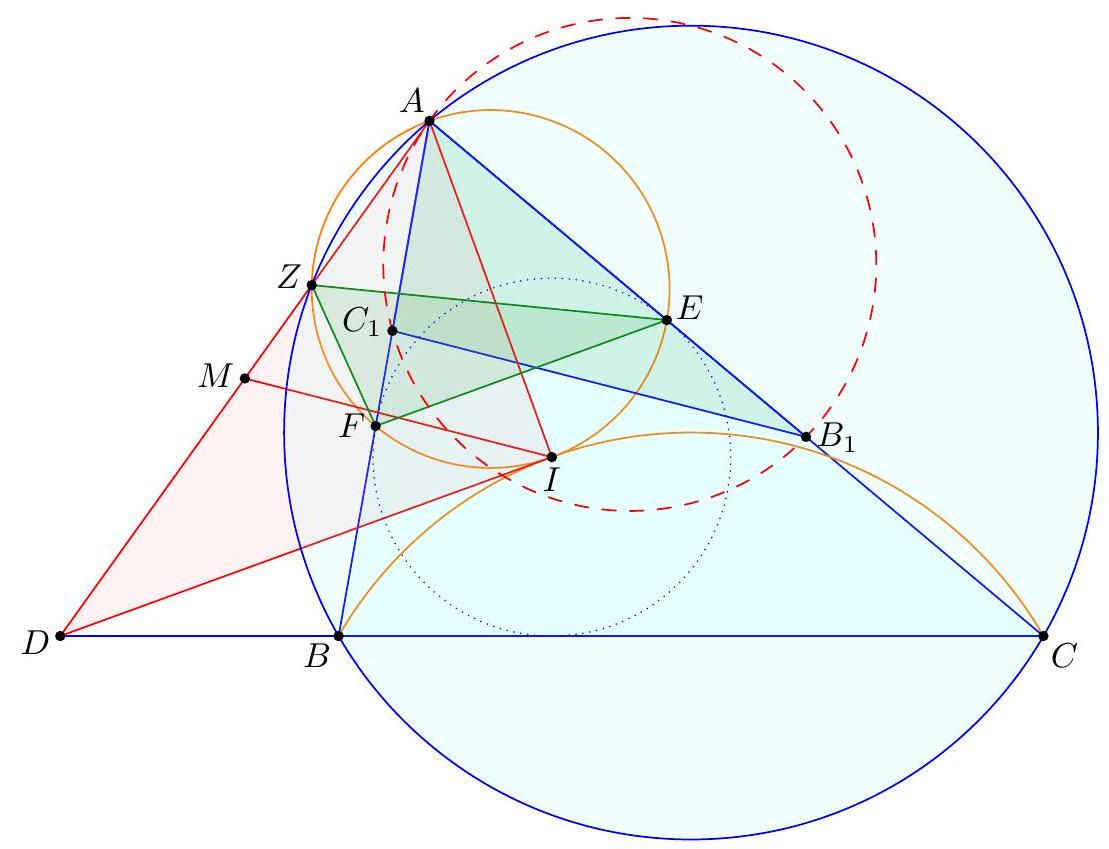

Point $D$ is selected inside acute triangle $A B C$ so that $\angle D A C=\angle A C B$ and $\angle B D C=90^{\circ}+\angle B A C$. Point $E$ is chosen on ray $B D$ so that $A E=E C$. Let $M$ be the midpoint of $B C$. Show that line $A B$ is tangent to the circumcircle of triangle $B E M$.

|

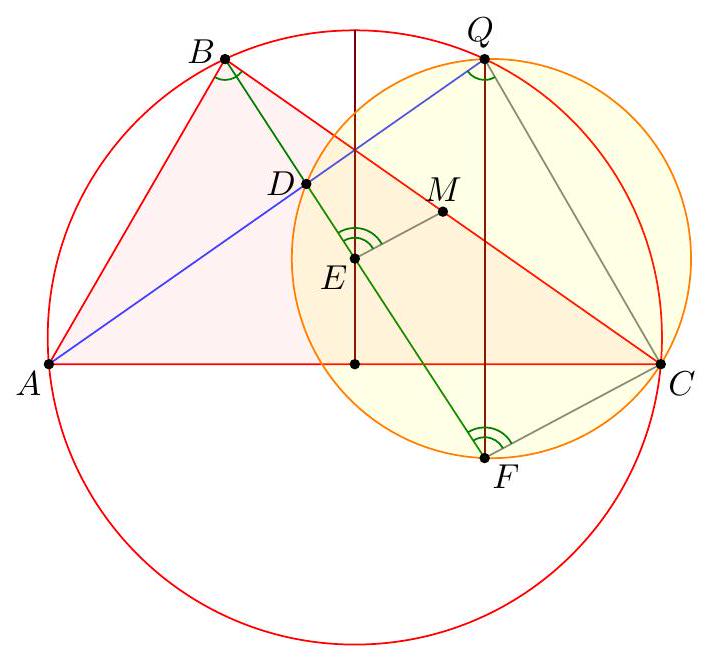

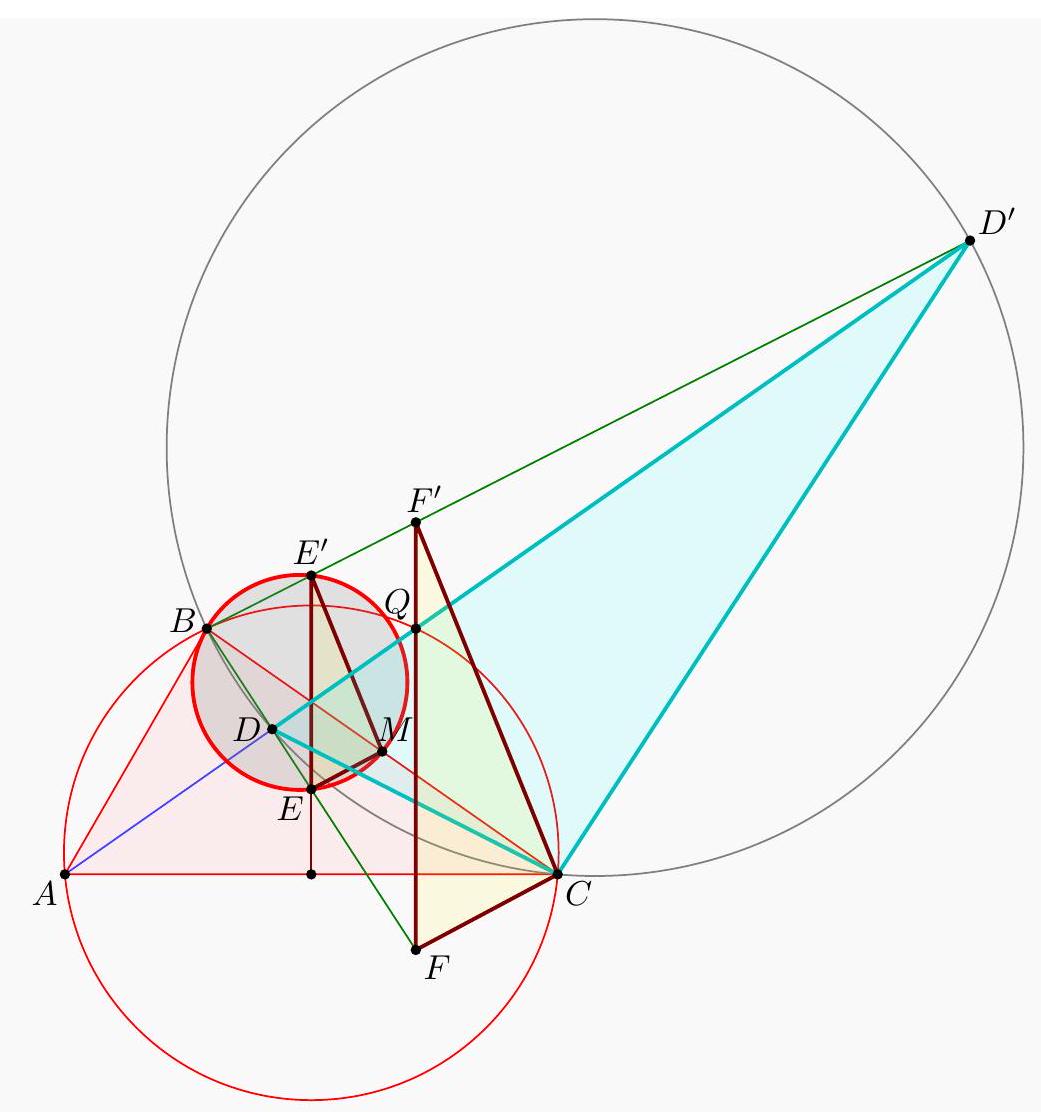

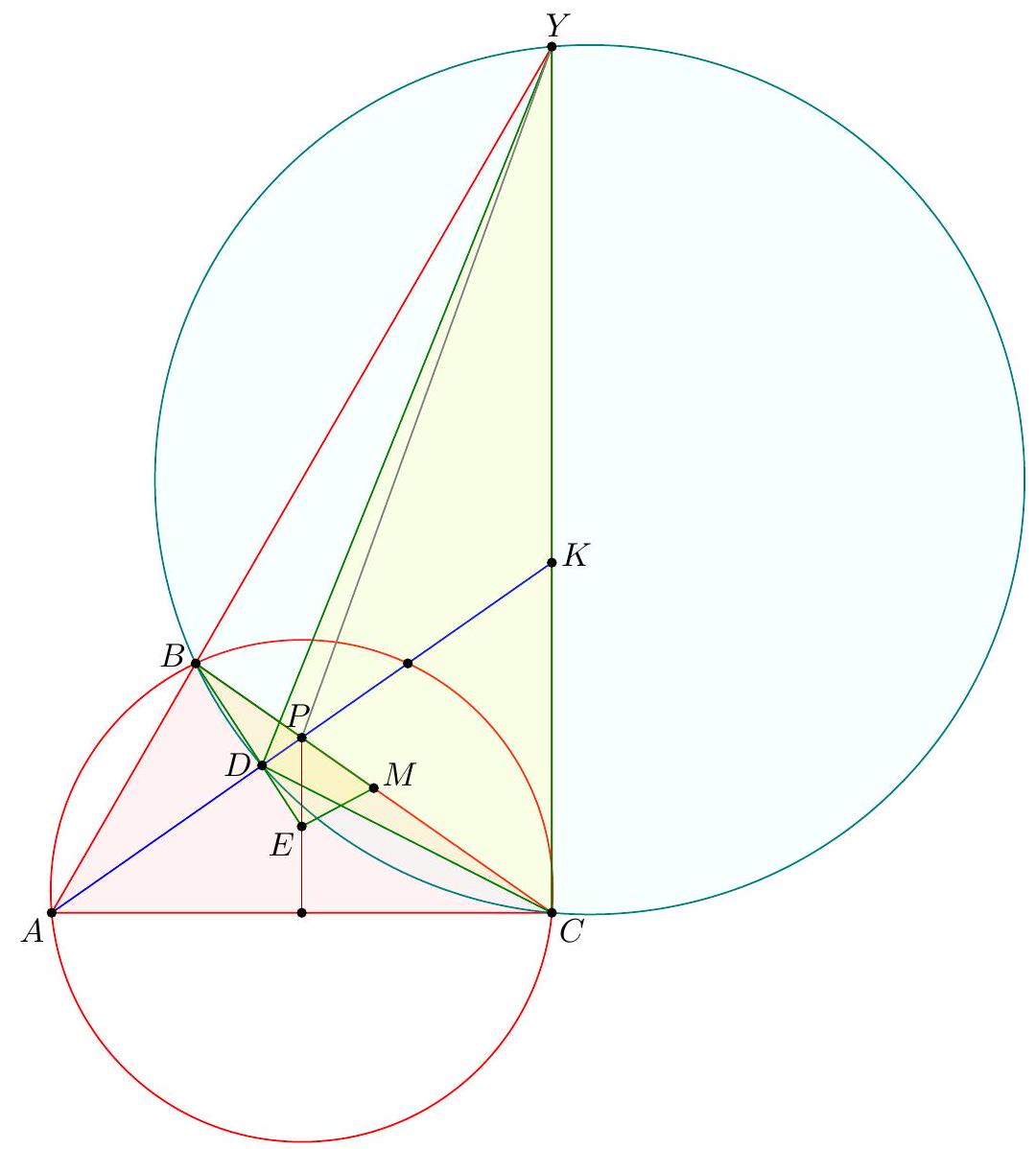

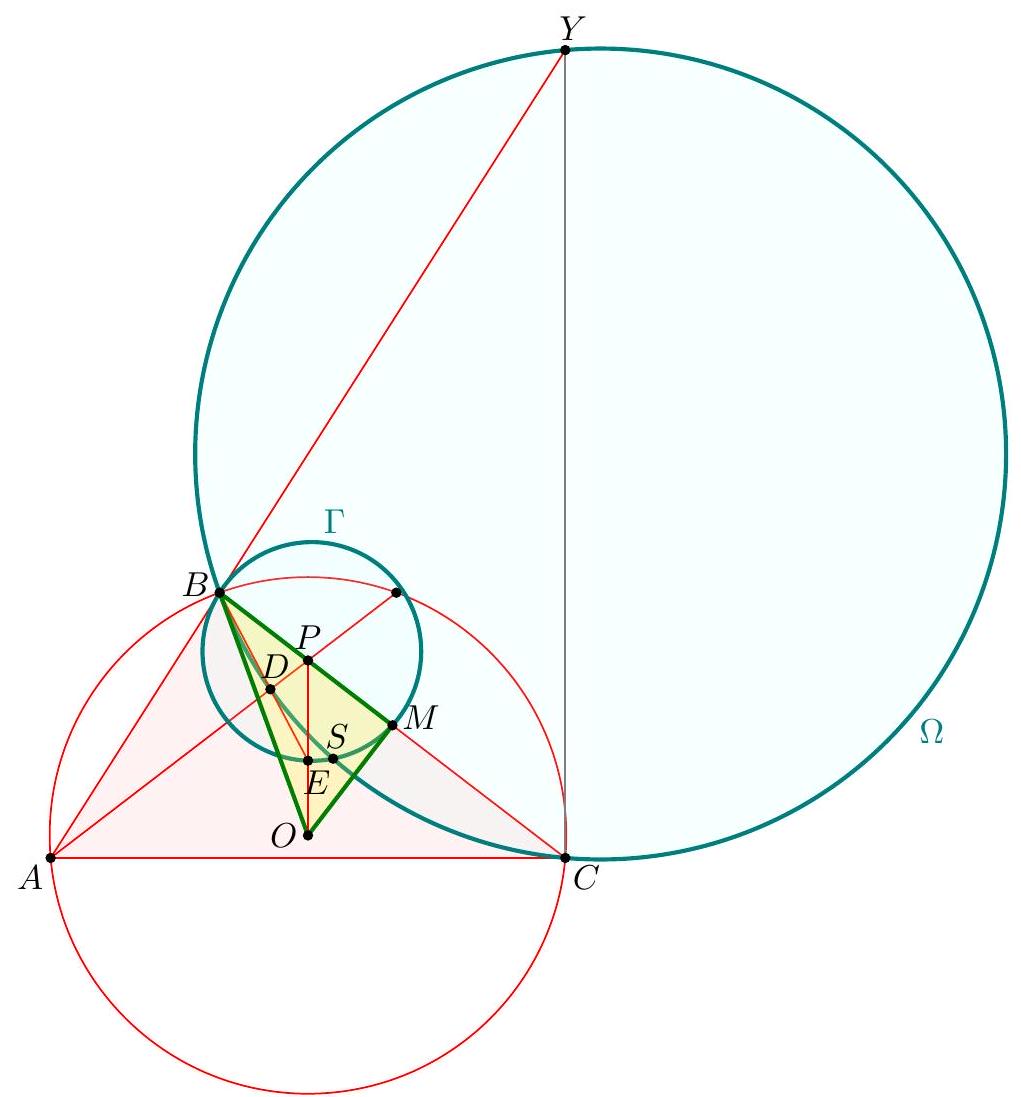

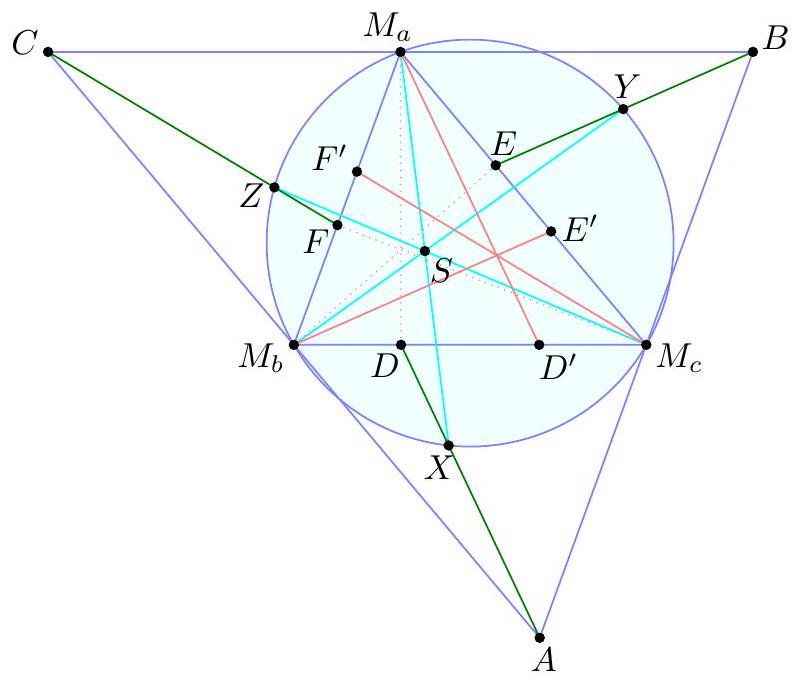

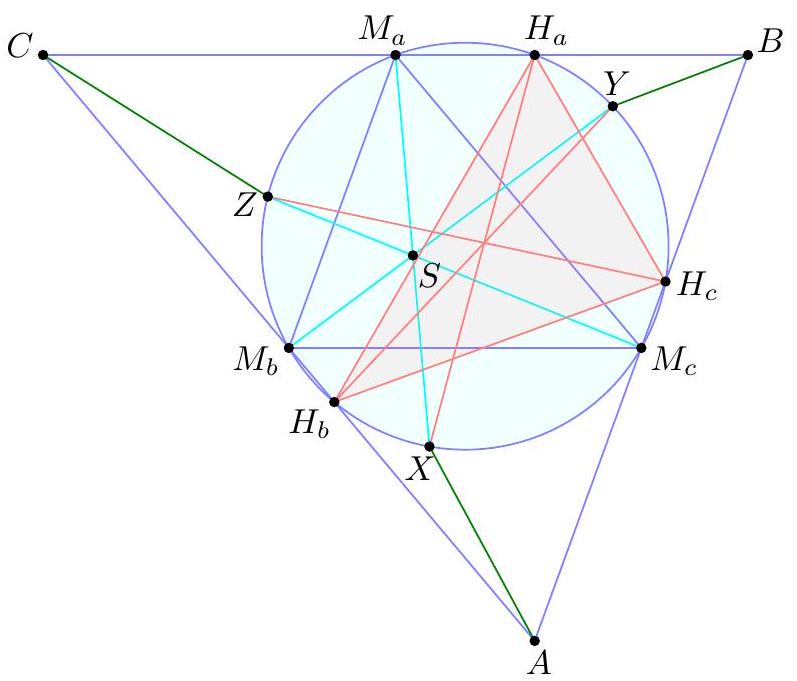

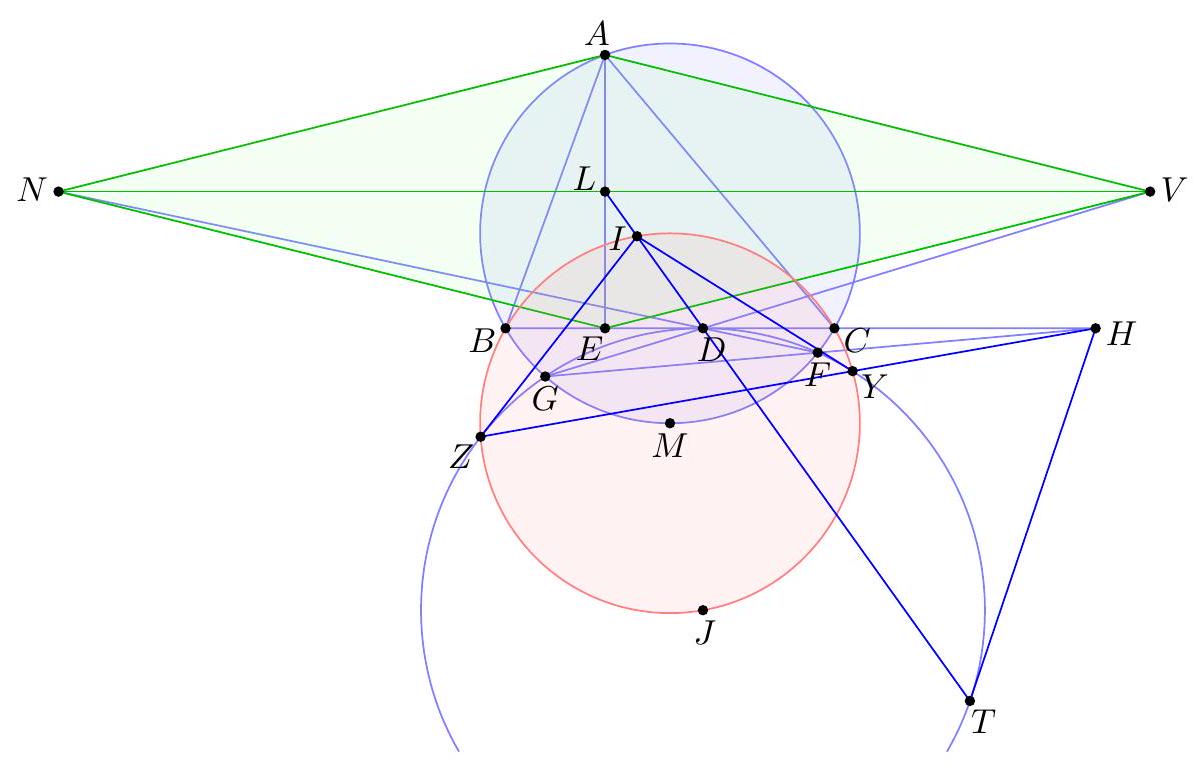

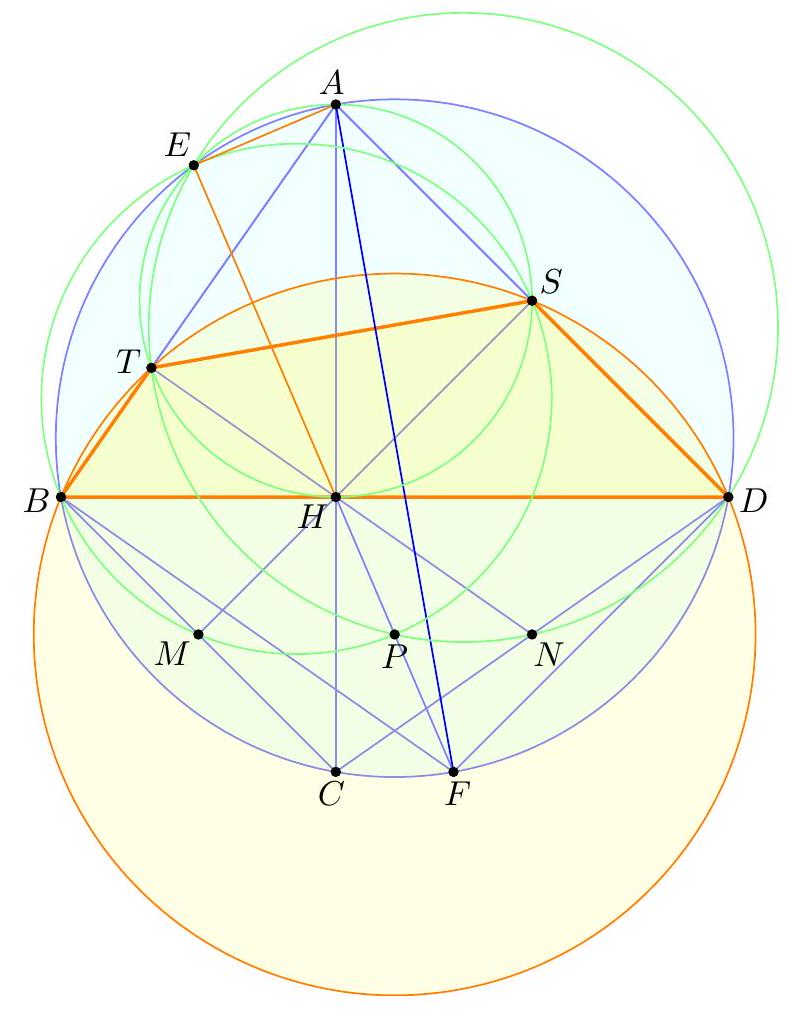

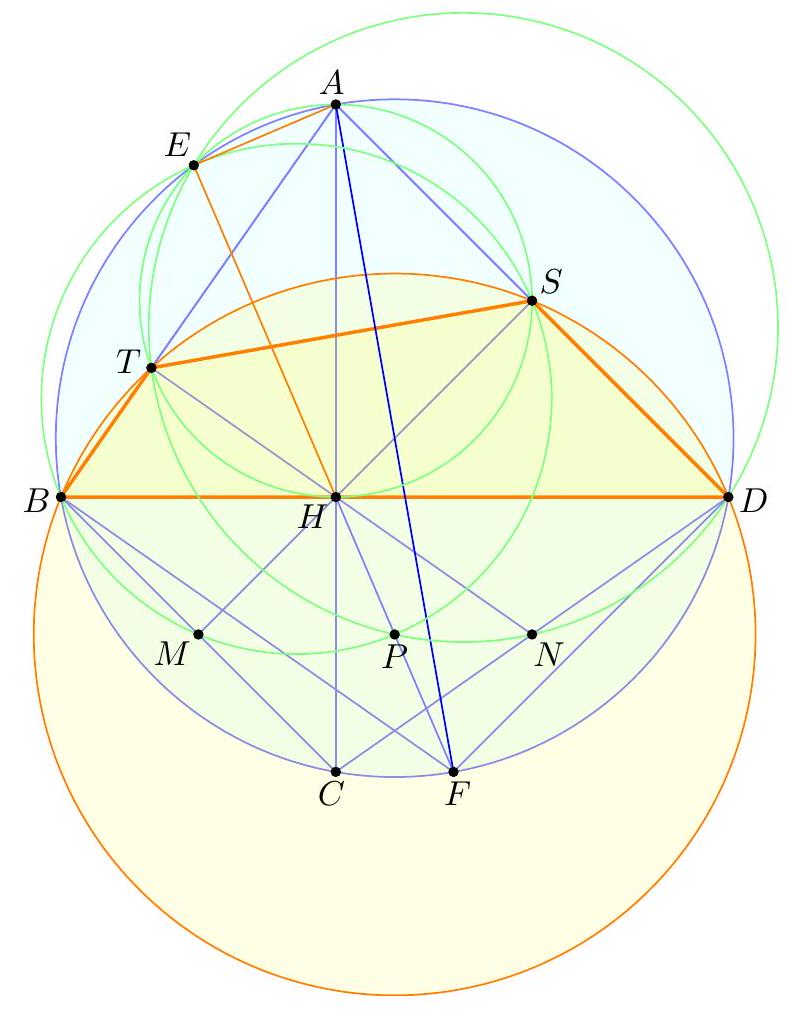

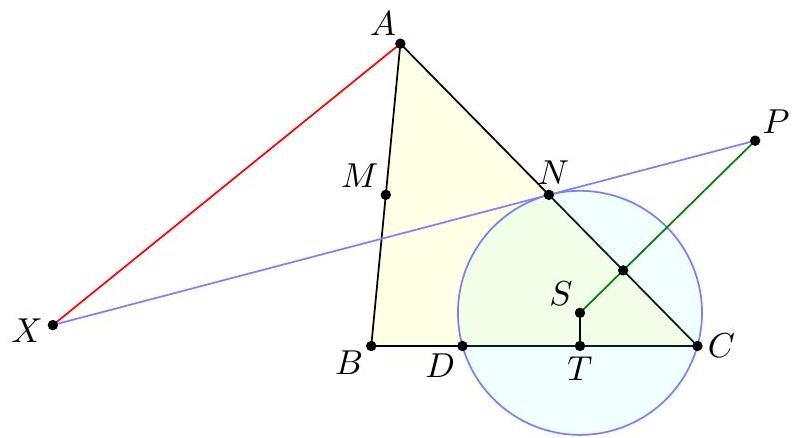

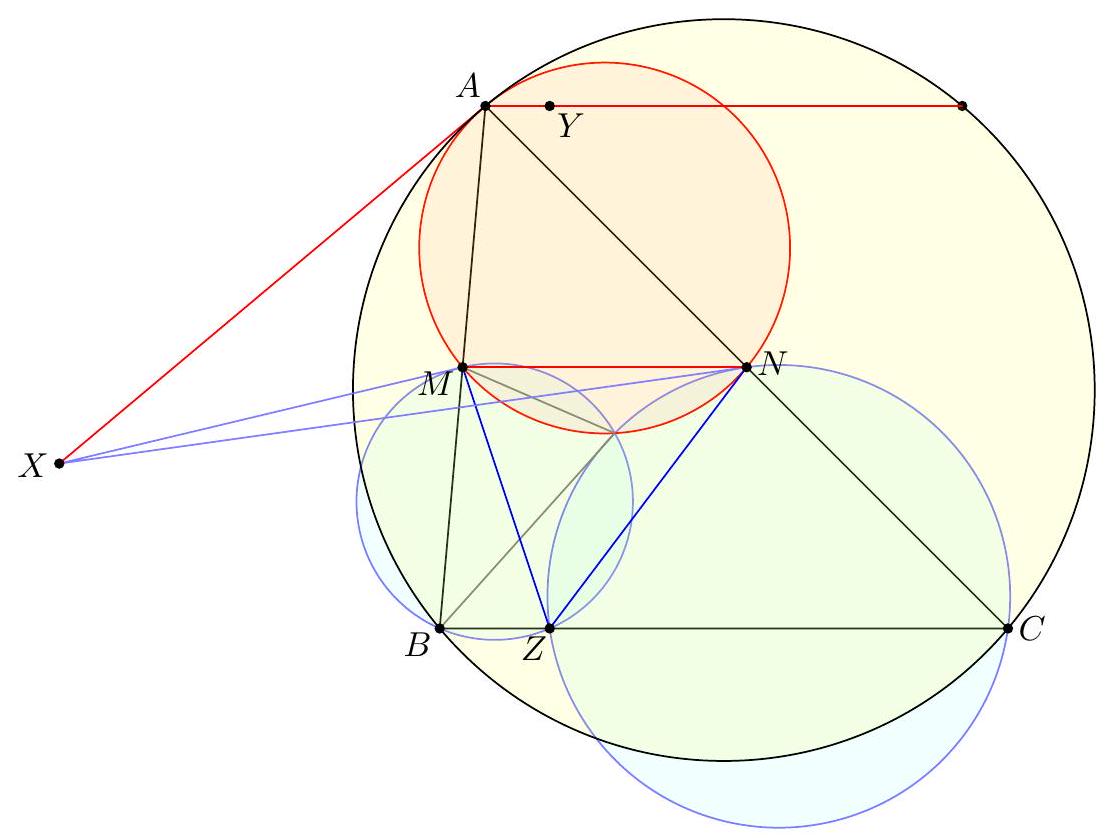

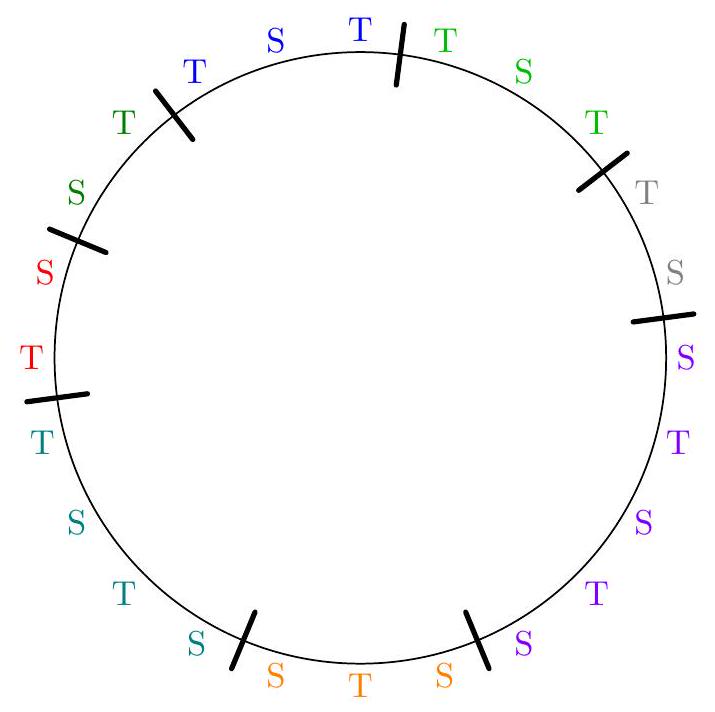

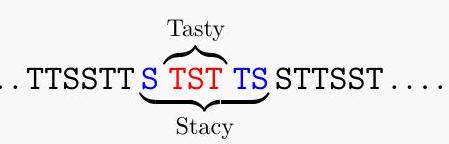

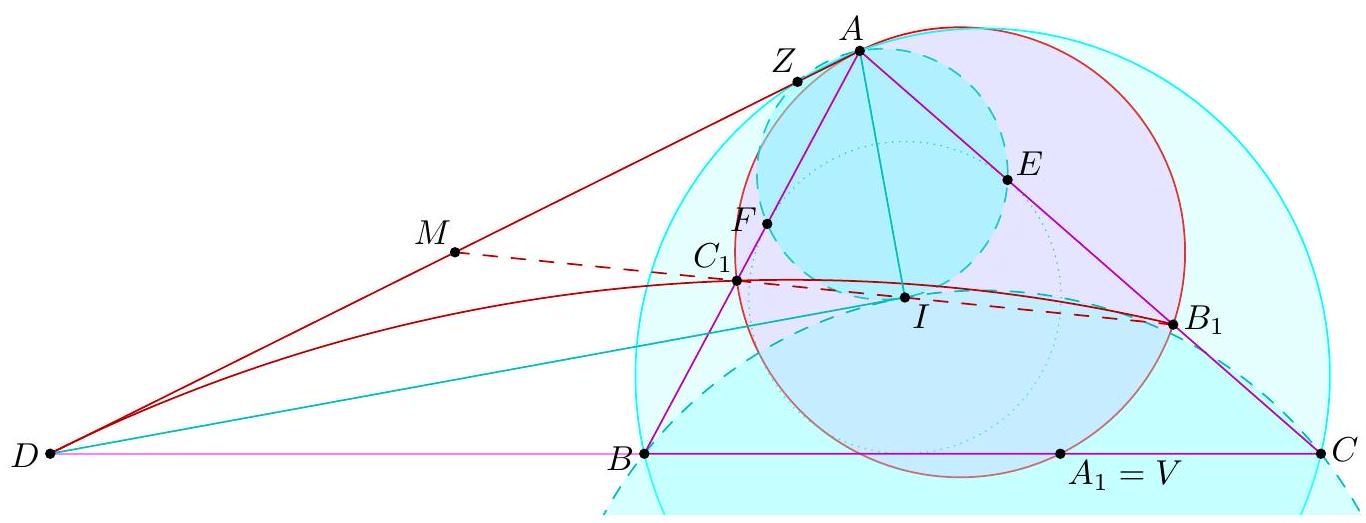

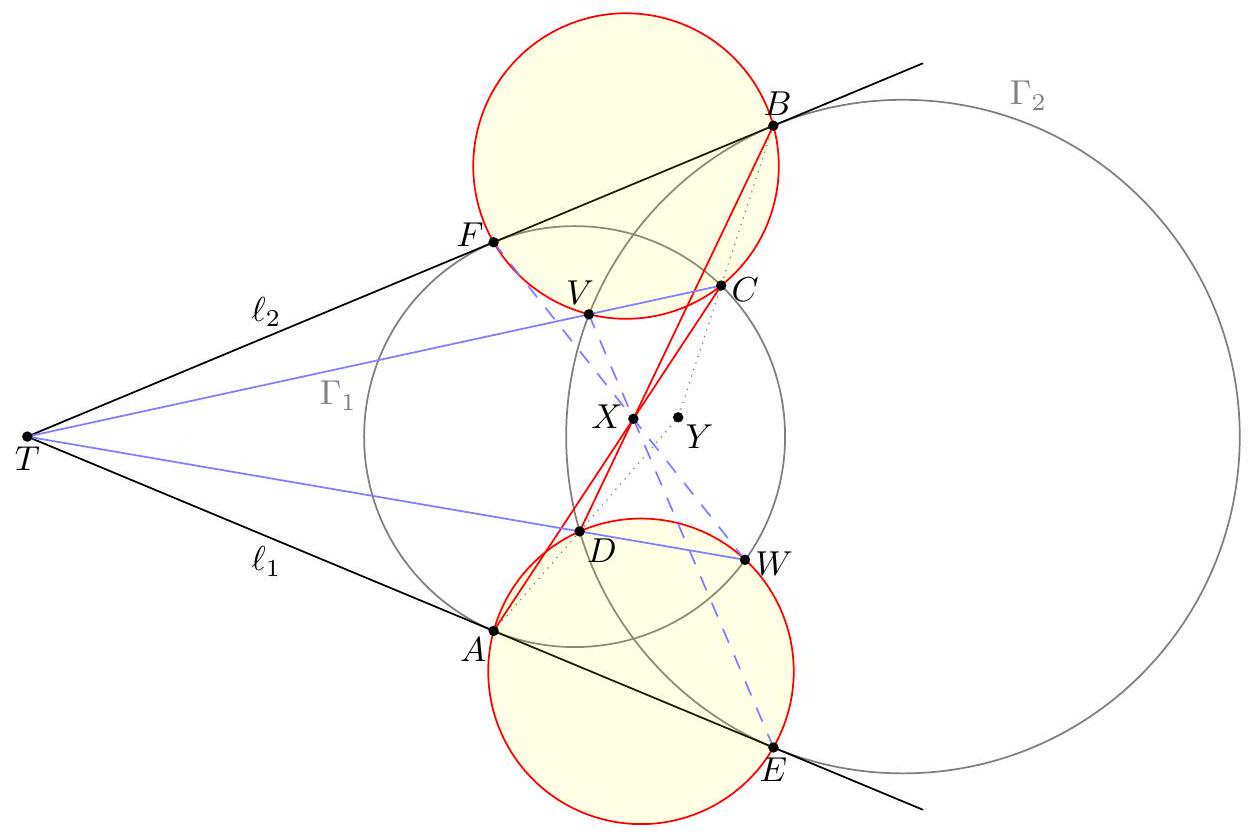

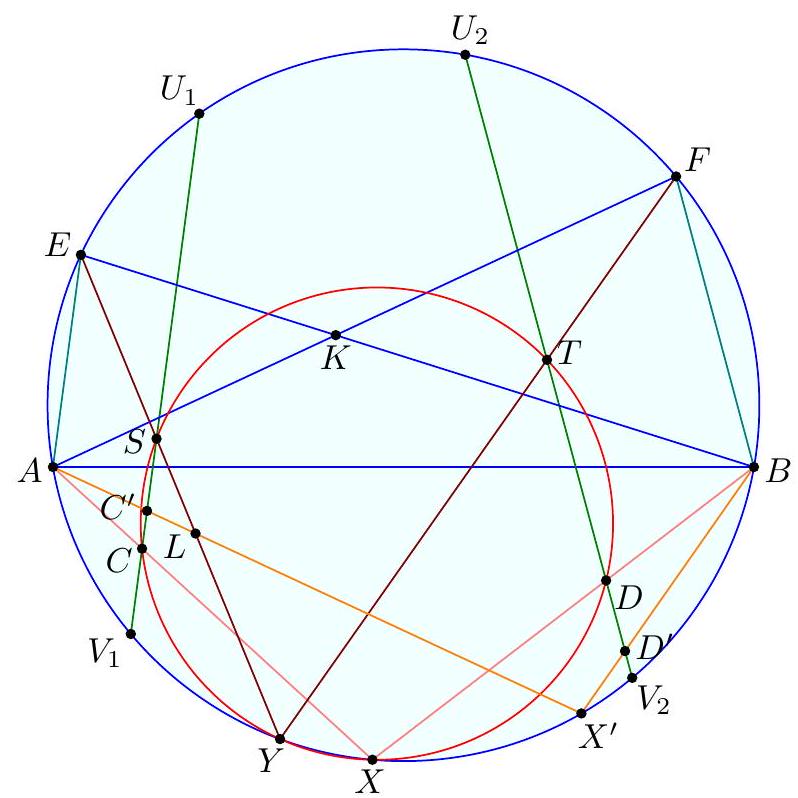

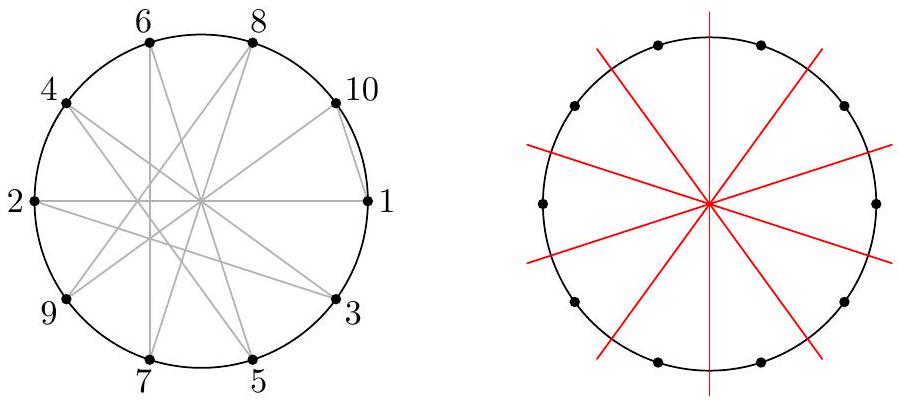

Claim - We have DQCF is cyclic. $$ \begin{aligned} \measuredangle F D C & =-\measuredangle C D B=180^{\circ}-\left(90^{\circ}+\measuredangle C A B\right)=90^{\circ}-\measuredangle C A B \\ & =90^{\circ}-\measuredangle Q C A=\measuredangle F Q C . \end{aligned} $$ To conclude, note that $$ \measuredangle B E M=\measuredangle B F C=\measuredangle D F C=\measuredangle D Q C=\measuredangle A Q C=\measuredangle A B C=\measuredangle A B M . $$ Remark (Motivation). Here is one possible way to come up with the construction of point $F$ (at least this is what led Evan to find it). If one directs all the angles in the obvious way, there are really two points $D$ and $D^{\prime}$ that are possible, although one is outside the triangle; they give corresponding points $E$ and $E^{\prime}$. The circles $B E M$ and $B E^{\prime} M$ must then actually coincide since they are both alleged to be tangent to line $A B$. See the figure below.  One can already prove using angle chasing that $\overline{A B}$ is tangent to $\left(B E E^{\prime}\right)$. So the point of the problem is to show that $M$ lies on this circle too. However, from looking at the diagram, one may realize that in fact it seems $$ \triangle M E E^{\prime} \stackrel{\triangle}{\sim} \triangle C D D^{\prime} $$ is going to be true from just those marked in the figure (and this would certainly imply the desired concyclic conclusion). Since $M$ is a midpoint, it makes sense to dilate $\triangle E M E^{\prime}$ from $B$ by a factor of 2 to get $\triangle F C F^{\prime}$ so that the desired similarity is actually a spiral similarity at $C$. Then the spiral similarity lemma says that the desired similarity is equivalent to requiring $\overline{D D^{\prime}} \cap \overline{F F^{\prime}}=Q$ to lie on both $(C D F)$ and $\left(C D^{\prime} F^{\prime}\right)$. Hence the key construction and claim from the solution are both discovered naturally, and we find the solution above. (The points $D^{\prime}, E^{\prime}, F^{\prime}$ can then be deleted to hide the motivation.) I A Menelaus-based approach (Kevin Ren). Let $P$ be on $\overline{B C}$ with $A P=P C$. Let $Y$ be the point on line $A B$ such that $\angle A C Y=90^{\circ}$; as $\angle A Y C=90^{\circ}-A$ it follows $B D Y C$ is cyclic. Let $K=\overline{A P} \cap \overline{C Y}$, so $\triangle A C K$ is a right triangle with $P$ the midpoint of its hypotenuse.  Claim - Triangles $B P E$ and $D Y K$ are similar. Claim - Triangles $B E M$ and $Y D C$ are similar. $$ \frac{B P}{B C} \frac{Y C}{Y K} \frac{A K}{A P}=1 $$ Since $A K / A P=2$ (note that $P$ is the midpoint of the hypotenuse of right triangle $A C K)$ and $B C=2 B M$, this simplifies to $$ \frac{B P}{B M}=\frac{Y K}{Y C} $$ To finish, note that $$ \measuredangle D B A=\measuredangle D B Y=\measuredangle D C Y=\measuredangle B M E $$ implying the desired tangency.  Denote by $S$ the second intersection of $\Gamma$ and $\Omega$. The main idea behind is to consider the spiral similarity $$ \Psi: \Omega \rightarrow \Gamma \quad C \mapsto M \text { and } Y \mapsto B $$ centered at $S$ (due to the spiral similarity lemma), and show that $\Psi(D)=E$. The spiral similarity lemma already promises $\Psi(D)$ lies on line $B D$. Claim - We have $\Psi(A)=O$, the circumcenter of $A B C$. Claim - $\Psi$ maps line $A D$ to line $O P$. $$ \measuredangle(\overline{A D}, \overline{O P})=\measuredangle A P O=\measuredangle O P C=\measuredangle Y C P=\measuredangle(\overline{Y C}, \overline{B M}) $$ As $\Psi$ maps line $Y C$ to line $B M$ and $\Psi(A)=O$, we're done. Hence $\Psi(D)$ should not only lie on $B D$ but also line $O P$. This proves $\Psi(D)=E$, so $E \in \Gamma$ as needed.

|

{

"resource_path": "USAMO/segmented/en-USAMO-2024-notes.jsonl",

"problem_match": null,

"solution_match": null

}

|

2024

|

T1

|

6

| null |

USAMO

|

Let $n>2$ be an integer and let $\ell \in\{1,2, \ldots, n\}$. A collection $A_{1}, \ldots, A_{k}$ of (not necessarily distinct) subsets of $\{1,2, \ldots, n\}$ is called $\ell$-large if $\left|A_{i}\right| \geq \ell$ for all $1 \leq i \leq k$. Find, in terms of $n$ and $\ell$, the largest real number $c$ such that the inequality $$ \sum_{i=1}^{k} \sum_{j=1}^{k} x_{i} x_{j} \frac{\left|A_{i} \cap A_{j}\right|^{2}}{\left|A_{i}\right| \cdot\left|A_{j}\right|} \geq c\left(\sum_{i=1}^{k} x_{i}\right)^{2} $$ holds for all positive integer $k$, all nonnegative real numbers $x_{1}, x_{2}, \ldots, x_{k}$, and all $\ell$-large collections $A_{1}, A_{2}, \ldots, A_{k}$ of subsets of $\{1,2, \ldots, n\}$.

|

The answer turns out to be $$ c=\frac{n+\ell^{2}-2 \ell}{n(n-1)} $$ 【 Rewriting as a dot product. For $i=1, \ldots, n$ define $\mathbf{v}_{i}$ by $$ \mathbf{v}_{i}[p, q]:=\left\{\begin{array}{ll} \frac{1}{\left|A_{i}\right|} & p \in A_{i} \text { and } q \in A_{i} \\ 0 & \text { otherwise; } \end{array} \quad \mathbf{v}:=\sum_{i} x_{i} \mathbf{v}_{i}\right. $$ Then $$ \begin{aligned} \sum_{i} \sum_{j} x_{i} x_{j} \frac{\left|A_{i} \cap A_{j}\right|^{2}}{\left|A_{i}\right|\left|A_{j}\right|} & =\sum_{i} \sum_{j} x_{i} x_{j}\left\langle\mathbf{v}_{i}, \mathbf{v}_{j}\right\rangle \\ & =\left\langle\sum_{i} x_{i} \mathbf{v}_{i}, \sum_{j} x_{i} \mathbf{v}_{i}\right\rangle=\left\|\sum_{i} x_{i} \mathbf{v}_{i}\right\|^{2}=\|\mathbf{v}\|^{2} . \end{aligned} $$ $$ \begin{aligned} & \langle\mathbf{e}, \mathbf{v}\rangle=\sum_{i} x_{i}\left\langle\mathbf{e}, \mathbf{v}_{i}\right\rangle=\sum_{i} x_{i} \\ & \langle\mathbf{1}, \mathbf{v}\rangle=\sum_{i} x_{i}\left\langle\mathbf{1}, \mathbf{v}_{i}\right\rangle=\sum_{i} x_{i}\left|A_{i}\right| . \end{aligned} $$ That means for any positive real constants $\alpha$ and $\beta$, by Cauchy-Schwarz for vectors, we should have $$ \begin{aligned} \|\alpha \mathbf{e}+\beta \mathbf{1}\|\|\mathbf{v}\| & \geq\langle\alpha \mathbf{e}+\beta \mathbf{1}, \mathbf{v}\rangle=\alpha\langle\mathbf{e}, \mathbf{v}\rangle+\beta\langle\mathbf{1}, \mathbf{v}\rangle \\ & =\alpha \cdot \sum x_{i}+\beta \cdot \sum x_{i}\left|A_{i}\right| \\ & \geq(\alpha+\ell \beta) \sum x_{i} . \end{aligned} $$ Set $\mathbf{w}:=\alpha \mathbf{e}+\beta \mathbf{1}$ for brevity. Then $$ \mathbf{w}[p, q]= \begin{cases}\alpha+\beta & \text { if } p=q \\ \beta & \text { if } p \neq q\end{cases} $$ SO $$ \|\mathbf{w}\|=\sqrt{n \cdot(\alpha+\beta)^{2}+\left(n^{2}-n\right) \cdot \beta^{2}} $$ Therefore, we get an lower bound $$ \frac{\|\mathbf{v}\|}{\sum x_{i}} \geq \frac{\alpha+\ell \beta}{\sqrt{n \cdot(\alpha+\beta)^{2}+\left(n^{2}-n\right) \cdot \beta^{2}}} $$ Letting $\alpha=n-\ell$ and $\beta=\ell-1$ gives a proof that the constant $$ c=\frac{((n-\ell)+\ell(\ell-1))^{2}}{n \cdot(n-1)^{2}+\left(n^{2}-n\right) \cdot(\ell-1)^{2}}=\frac{\left(n+\ell^{2}-2 \ell\right)^{2}}{n(n-1)\left(n+\ell^{2}-2 \ell\right)}=\frac{n+\ell^{2}-2 \ell}{n(n-1)} $$ makes the original inequality always true. (The choice of $\alpha: \beta$ is suggested by the example below.) 【 Example showing this $c$ is best possible. Let $k=\binom{n}{\ell}$, let $A_{i}$ run over all $\binom{n}{\ell}$ subsets of $\{1, \ldots, n\}$ of size $\ell$, and let $x_{i}=1$ for all $i$. We claim this construction works. To verify this, it would be sufficient to show that $\mathbf{w}$ and $\mathbf{v}$ are scalar multiples, so that the above Cauchy-Schwarz is equality. However, we can compute $$ \mathbf{w}[p, q]=\left\{\begin{array}{ll} n-1 & \text { if } p=q \\ \ell-1 & \text { if } p \neq q \end{array}, \quad \mathbf{v}[p, q]= \begin{cases}\binom{n-1}{\ell-1} \cdot \frac{1}{\ell} & \text { if } p=q \\ \binom{n-2}{\ell-2} \cdot \frac{1}{\ell} & \text { if } p \neq q\end{cases}\right. $$ which are indeed scalar multiples, finishing the proof.

|

{

"resource_path": "USAMO/segmented/en-USAMO-2024-notes.jsonl",

"problem_match": null,

"solution_match": null

}

|

2025

|

T1

|

1

| null |

USAMO

|

Fix positive integers \(k\) and \(d\) . Prove that for all sufficiently large odd positive integers \(n\) , the digits of the base-2 \(n\) representation of \(n^{k}\) are all greater than \(d\) .

|

The problem actually doesn't have much to do with digits: the idea is to pick any length \(\ell \leq k\) , and look at the rightmost \(\ell\) digits of \(n^{k}\) ; that is, the remainder upon division by \((2n)^{\ell}\) . We compute it exactly:

Claim — Let \(n \geq 1\) be an odd integer, and \(k \geq \ell \geq 1\) integers. Then

\[n^{k} \bmod (2n)^{i} = c(k, \ell) \cdot n^{i}\]

for some odd integer \(1 \leq c(k, \ell) \leq 2^{\ell} - 1\) .

Proof. This follows directly by the Chinese remainder theorem, with \(c(k, \ell)\) being the residue class of \(n^{k - i} \pmod{2^{\ell}}\) (which makes sense because \(n\) was odd). \(\square\)

We can now stake the required threshold:

Claim — The problem statement holds once \(n \geq (d + 1) \cdot 2^{k - 1}\) .

Proof. Suppose \(n\) is that large. Then \(n^{k}\) has \(k\) digits in base- \(2n\) . Moreover, for each \(1 \leq \ell \leq k\) we have

\[c(k, \ell) \cdot n^{\ell} \geq (d + 1) \cdot (2n)^{\ell - 1}\]

because \(n\) is large enough; that implies the \(\ell^{\mathrm{th}}\) digit from the right is at least \(d + 1\) . Hence the problem is solved. \(\square\)

Remark. Note it doesn't really matter that \(c(k, i)\) is odd per se; we only need that \(c(k, i) \geq 1\) .

|

{

"resource_path": "USAMO/segmented/en-USAMO-2025-notes.jsonl",

"problem_match": "1. ",

"solution_match": "## \\(\\S 1.1\\) USAMO 2025/1, proposed by John Berman \n"

}

|

2025

|

T1

|

2

| null |

USAMO

|

Let \(n > k \geq 1\) be integers. Let \(P(x) \in \mathbb{R}[x]\) be a polynomial of degree \(n\) with no repeated roots and \(P(0) \neq 0\) . Suppose that for any real numbers \(a_0, \ldots , a_k\) such that the polynomial \(a_k x^k + \dots + a_1 x + a_0\) divides \(P(x)\) , the product \(a_0 a_1 \ldots a_k\) is zero. Prove that \(P(x)\) has a nonreal root.

|

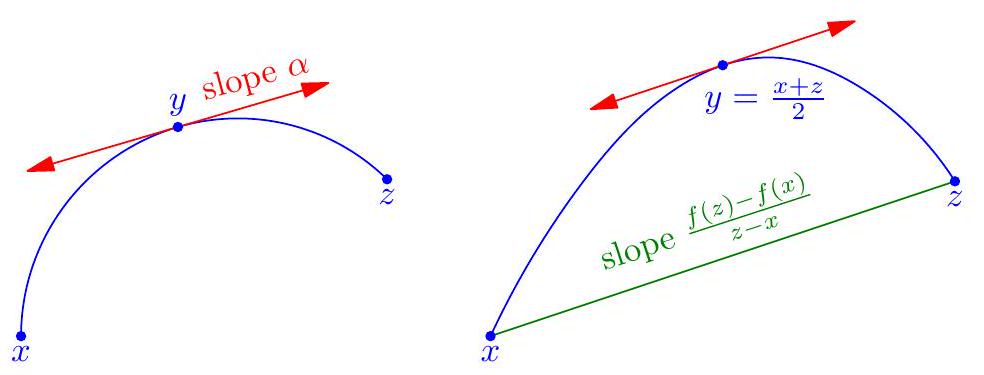

By considering any \(k + 1\) of the roots of \(P\) , we may as well assume WLOG that \(n = k + 1\) . Suppose that \(P(x) = (x + r_{1})\ldots (x + r_{n})\in \mathbb{R}[x]\) has \(P(0)\neq 0\) . Then the problem hypothesis is that each of the \(n\) polynomials (of degree \(n - 1\) ) given by

\[P_{1}(x) = (x + r_{2})(x + r_{3})(x + r_{4})\ldots (x + r_{n})\] \[P_{2}(x) = (x + r_{1})(x + r_{3})(x + r_{4})\ldots (x + r_{n})\] \[P_{3}(x) = (x + r_{1})(x + r_{2})(x + r_{4})\ldots (x + r_{n})\] \[\vdots\] \[P_{n}(x) = (x + r_{1})(x + r_{2})(x + r_{3})\ldots (x + r_{n - 1})\]

has at least one coefficient equal to zero. (Explicitly, \(P_{i}(x) = \frac{P(x)}{x + r_{i}}\) .) We'll prove that at least one \(r_{i}\) is not real.

Obviously the leading and constant coefficients of each \(P_{i}\) are nonzero, and there are \(n - 2\) other coefficients to choose between. So by pigeonhole principle, we may assume, say, that \(P_{1}\) and \(P_{2}\) share the position of a zero coefficient, say the \(x^{k}\) one, for some \(1\leq k< n - 1\)

Claim — If \(P_{1}\) and \(P_{2}\) both have \(x^{k}\) coefficient equal to zero, then the polynomial

\[Q(x) = (x + r_{3})(x + r_{4})\ldots (x + r_{n})\]

has two consecutive zero coefficients, namely \(b_{k} = b_{k - 1} = 0\)

Proof. Invoking Vieta formulas, suppose that

\[Q(x) = x^{n - 2} + b_{n - 3}x^{n - 3} + \dots +b_{0}.\]

(And let \(b_{n - 2} = 1\) .) Then the fact that the \(x^{k}\) coefficient of \(P_{1}\) and \(P_{2}\) are both zero means

\[r_{1}b_{k} + b_{k - 1} = r_{2}b_{k} + b_{k - 1} = 0\]

and hence that \(b_{k} = b_{k - 1} = 0\) (since the \(r_{i}\) are nonzero).

To solve the problem, we use:

## Lemma

If \(F(x)\in \mathbb{R}[x]\) is a polynomial with two consecutive zero coefficients, it cannot have all distinct real roots.

Here are two possible proofs of the lemma I know (there are more).

First proof using Rolle's theorem. Say \(x^{t}\) and \(x^{t + 1}\) coefficients of \(F\) are both zero.

Assume for contradiction all the roots of \(F\) are real and distinct. Then by Rolle's theorem, every higher- order derivative of \(F\) should have this property too. However, the \(t\) th order derivative of \(F\) has a double root of 0, contradiction. \(\square\)

Second proof using Descartes rule of signs. The number of (nonzero) roots of \(F\) is bounded above by the number of sign changes of \(F(x)\) (for the positive roots) and the number of sign changes of \(F(- x)\) (for the negative roots). Now consider each pair of consecutive nonzero coefficients in \(F\) , say \(x x^{i}\) and \(x x^{j}\) for \(i > j\) .

- If \(i - j = 1\) , then this sign change will only count for one of \(F(x)\) or \(F(-x)\)

- If \(i - j \geq 2\) , then the sign change could count towards both \(F(x)\) or \(F(-x)\) (i.e. counted twice), but also there is at least one zero coefficient between them.

Hence if \(b\) is the number of nonzero coefficients of \(F\) , and \(z\) is the number of consecutive runs of zero coefficients of \(F\) , then the number of real roots is bounded above by

\[1\cdot (b - 1 - z) + 2\cdot z = b - 1 + z\leq \deg F.\]

However, if \(F\) has two consecutive zero coefficients, then the inequality is strict. \(\square\)

Remark. The final claim has appeared before apparently in the HUST Team Selection Test for the Vietnamese Math Society's undergraduate olympiad; see https://aops.com/ community/p33893374 for citation.

|

{

"resource_path": "USAMO/segmented/en-USAMO-2025-notes.jsonl",

"problem_match": "2. ",

"solution_match": "## \\(\\S 1.2\\) USAMO 2025/2, proposed by Carl Schildkraut \n"

}

|

2025

|

T1

|

3

| null |

USAMO

|

Alice the architect and Bob the builder play a game. First, Alice chooses two points \(P\) and \(Q\) in the plane and a subset \(S\) of the plane, which are announced to Bob. Next, Bob marks infinitely many points in the plane, designating each a city. He may not place two cities within distance at most one unit of each other, and no three cities he places may be collinear. Finally, roads are constructed between the cities as follows: each pair \(A\) , \(B\) of cities is connected with a road along the line segment \(AB\) if and only if the following condition holds:

For every city \(C\) distinct from \(A\) and \(B\) , there exists \(R \in S\) such that

\(\triangle PQR\) is directly similar to either \(\triangle ABC\) or \(\triangle BAC\) .

Alice wins the game if (i) the resulting roads allow for travel between any pair of cities via a finite sequence of roads and (ii) no two roads cross. Otherwise, Bob wins. Determine, with proof, which player has a winning strategy.

|

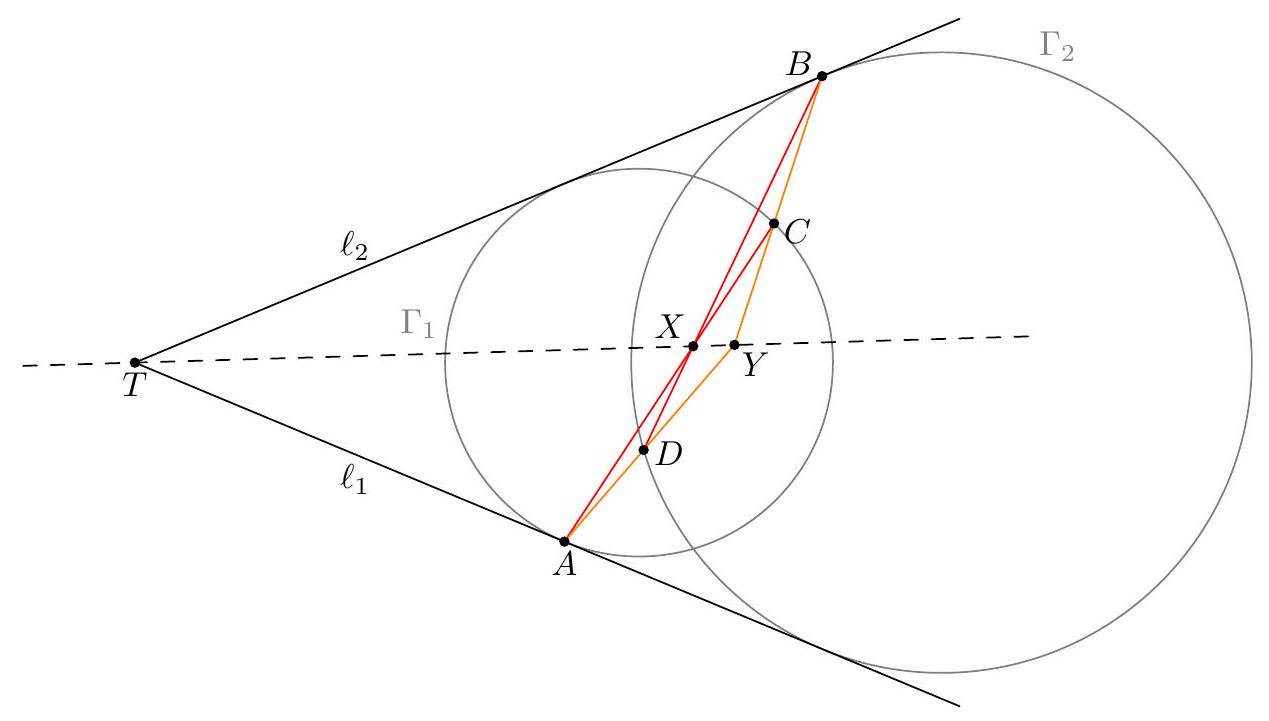

The answer is that Alice wins. Let's define a Bob- set \(V\) to be a set of points in the plane with no three collinear and with all distances at least 1. The point of the problem is to prove the following fact.

Claim — Given a Bob- set \(V\subseteq \mathbb{R}^{2}\) , consider the Bob- graph with vertex set \(V\) defined as follows: draw edge \(ab\) if and only if the disk with diameter \(\overline{ab}\) contains no other points of \(V\) on or inside it. Then the Bob- graph is (i) connected, and (ii) planar.

Proving this claim shows that Alice wins since Alice can specify \(S\) to be the set of points outside the disk of diameter \(PQ\) .

Proof that every Bob- graph is connected. Assume for contradiction the graph is disconnected. Let \(p\) and \(q\) be two points in different connected components. Since \(pq\) is not an edge, there exists a third point \(r\) inside the disk with diameter \(\overline{pq}\) .

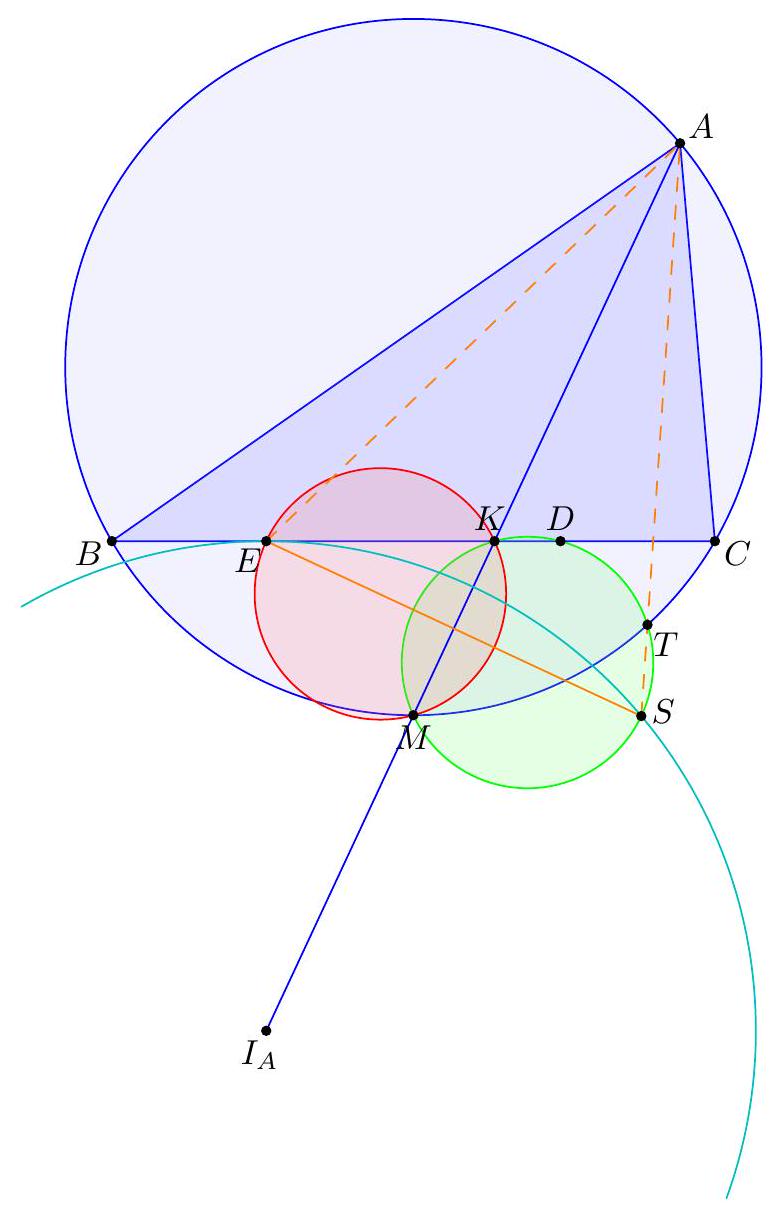

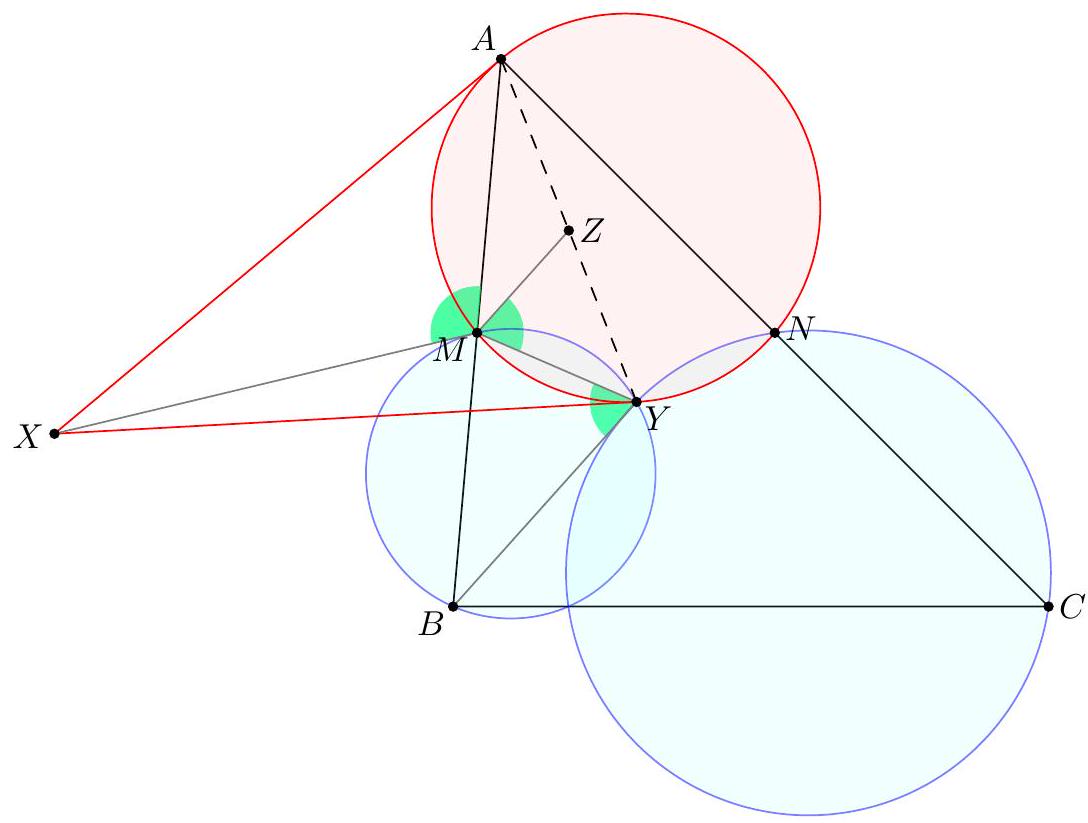

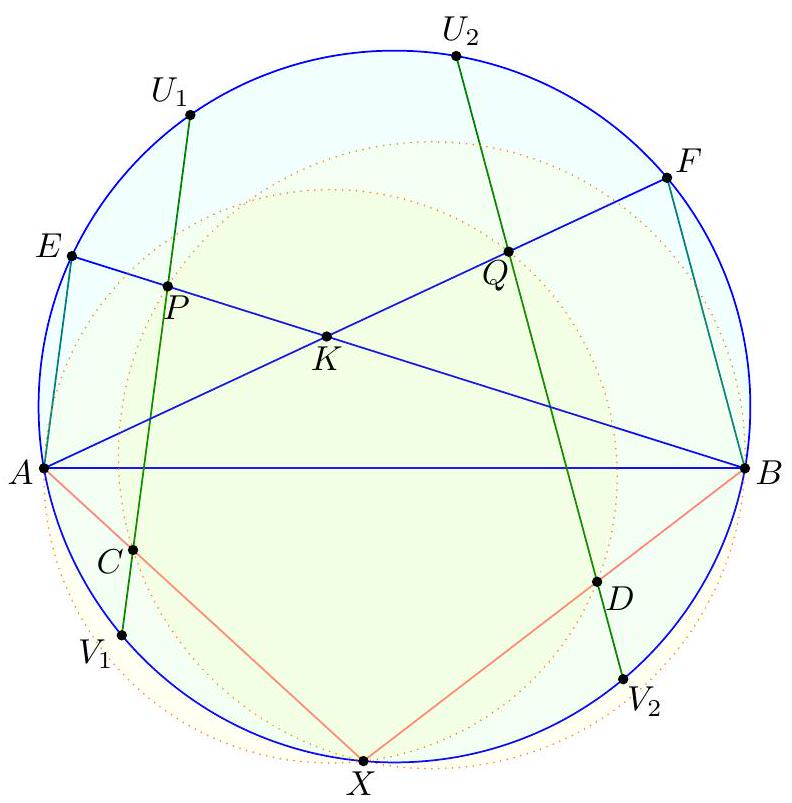

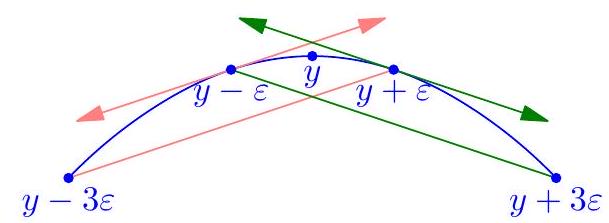

Hence, \(r\) is in a different connected component from at least one of \(p\) or \(q\) — let's say point \(p\) . Then we repeat the same argument on the disk with diameter \(\overline{pr}\) to find a new point \(s\) , non- adjacent to either \(p\) or \(r\) . See the figure below, where the \(X\) 'ed out dashed edges indicate points which are not only non- adjacent but in different connected components.

In this way we generate an infinite sequence of distances \(\delta_{1}\) , \(\delta_{2}\) , \(\delta_{3}\) , ... among the non- edges in the picture above. By the "Pythagorean theorem" (or really the inequality for it), we have

\[\delta_{i}^{2}\leq \delta_{i - 1}^{2} - 1\]

and this eventually generates a contradiction for large \(i\) , since we get \(0 \leq \delta_{i}^{2} \leq \delta_{1}^{2} - (i - 1)\) . \(\square\)

Proof that every Bob- graph is planar. Assume for contradiction edges \(ac\) and \(bd\) meet, meaning \(abcd\) is a convex quadrilateral. WLOG assume \(\angle bad \geq 90^{\circ}\) (each quadrilateral has an angle at least \(90^{\circ}\) ). Then the disk with diameter \(\overline{bd}\) contains \(a\) , contradiction. \(\square\)

Remark. In real life, the Bob- graph is actually called the Gabriel graph. Note that we never require the Bob- set to be infinite; the solution works unchanged for finite Bob- sets.

However, there are approaches that work for finite Bob- sets that don't work for infinite sets, such as the relative neighbor graph, in which one joins \(a\) and \(b\) iff there is no \(c\) such that \(d(a,b) \leq \max \{d(a,c),d(b,c)\}\) . In other words, edges are blocked by triangles where \(ab\) is the longest edge (rather than by triangles where \(ab\) is the longest edge of a right or obtuse triangle as in the Gabriel graph).

The relative neighbor graph has fewer edges than the Gabriel graph, so it is planar too. When the Bob- set is finite, the relative distance graph is still connected. The same argument above works where the distances now satisfy

\[\delta_{1} > \delta_{2} > \ldots\]

instead, and since there are finitely many distances one arrives at a contradiction.

However for infinite Bob- sets the descending condition is insufficient, and connectedness actually fails altogether. A counterexample (communicated to me by Carl Schildkraut) is to start by taking \(A_{n} \approx (2n,0)\) and \(B_{n} \approx (2n + 1,\sqrt{3})\) for all \(n \geq 1\) , then perturb all the points slightly so that

\[B_{1}A_{1} > A_{1}A_{2} > A_{2}B_{1} > B_{1}B_{2} > B_{2}A_{2\] \[> A_{2}A_{3} > A_{3}B_{2} > B_{2}B_{3} > B_{3}A_{3\] \[> \dots\]

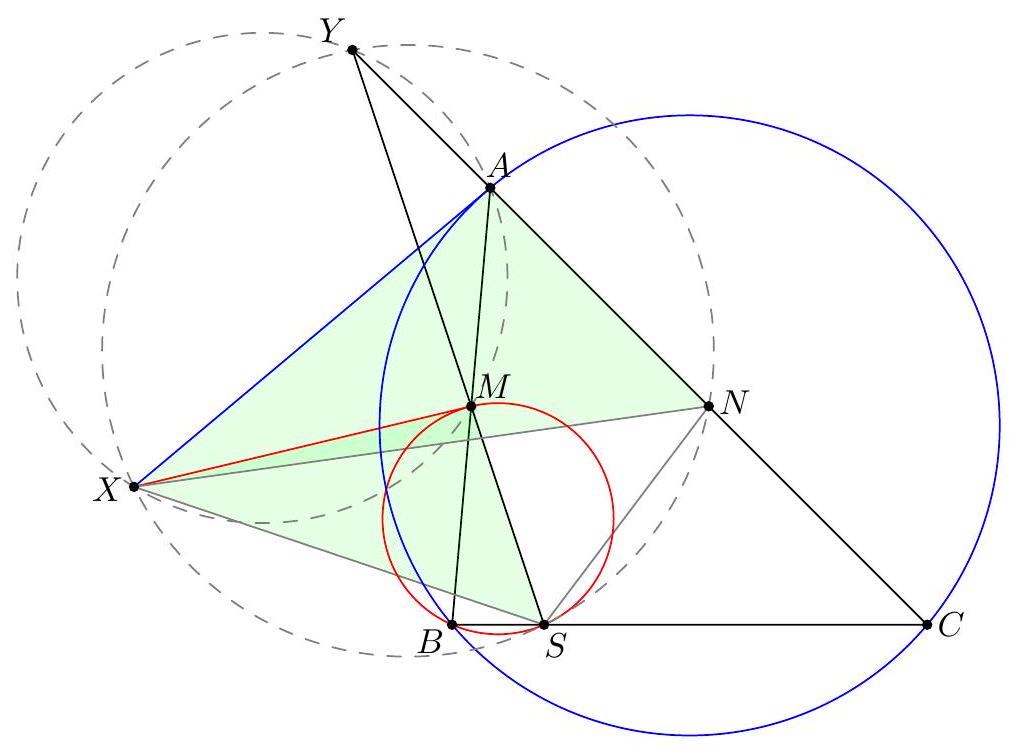

A cartoon of the graph is shown below.

In that case, \(\{A_{n}\}\) and \(\{B_{n}\}\) will be disconnected from each other: none of the edges \(A_{n}B_{n}\) or \(B_{n}A_{n + 1}\) are formed. In this case the relative neighbor graph consists of the edges \(A_{1}A_{2}A_{3}A_{4}\dots\) and \(B_{1}B_{2}B_{3}B_{4}\dots\) . That's why for the present problem, the inequality

\[\delta_{i}^{2}\leq \delta_{i - 1}^{2} - 1\]

plays such an important role, because it causes the (squared) distances to decrease appreciably enough to give the final contradiction.

## \(\S 2\) Solutions to Day 2

|

{

"resource_path": "USAMO/segmented/en-USAMO-2025-notes.jsonl",

"problem_match": "3. ",

"solution_match": "## \\(\\S 1.3\\) USAMO 2025/3, proposed by Carl Schildkraut \n"

}

|

2025

|

T1

|

4

| null |

USAMO

|

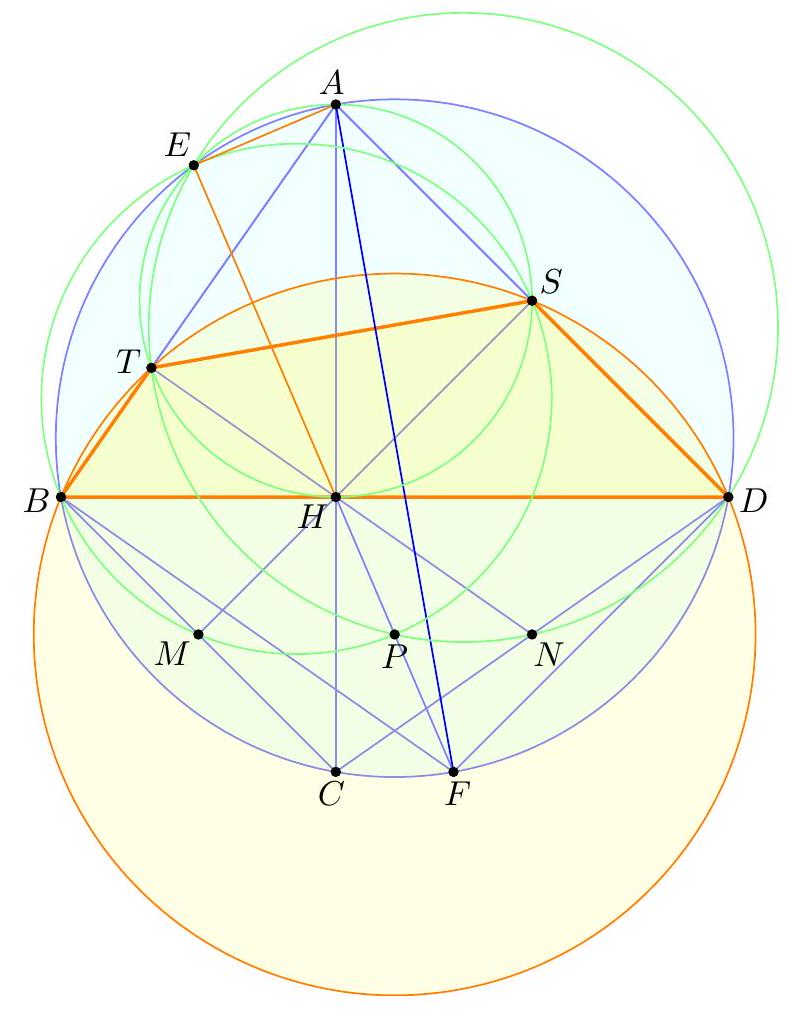

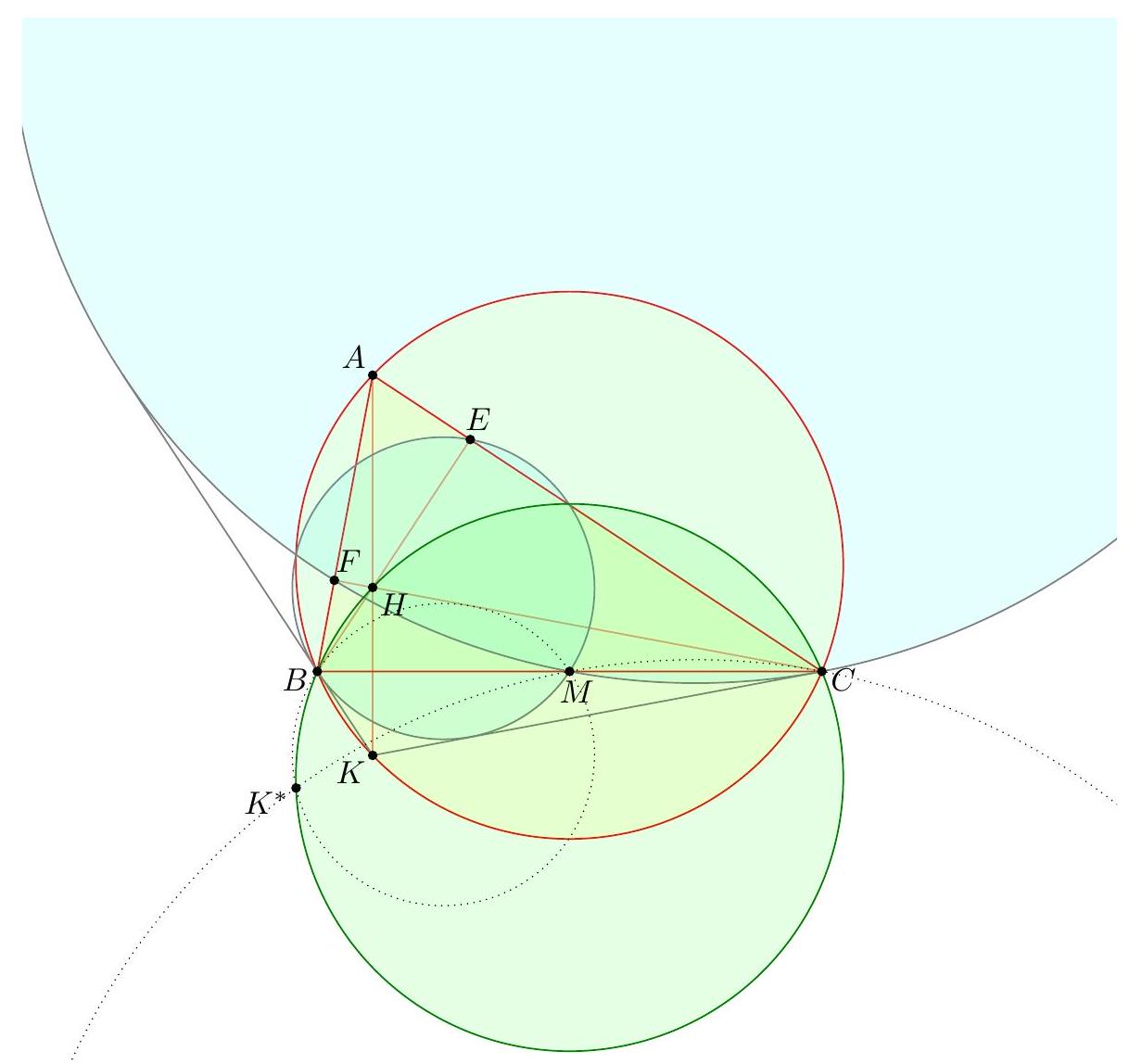

Let \(H\) be the orthocenter of an acute triangle \(ABC\) , let \(F\) be the foot of the altitude from \(C\) to \(AB\) , and let \(P\) be the reflection of \(H\) across \(BC\) . Suppose that the circumcircle of triangle \(AFP\) intersects line \(BC\) at two distinct points \(X\) and \(Y\) . Prove that \(CX = CY\) .

|

Let \(Q\) be the antipode of \(B\) .

Claim — \(AHQC\) is a parallelogram, and \(APCQ\) is an isosceles trapezoid.

Proof. As \(\overline{AH} \perp \overline{BC} \perp \overline{CQ}\) and \(\overline{CF} \perp \overline{AB} \perp \overline{AQ}\) .

Let \(M\) be the midpoint of \(\overline{QC}\) .

Claim — Point \(M\) is the circumcenter of \(\triangle AFP\) .

Proof. It's clear that \(MA = MP\) from the isosceles trapezoid. As for \(MA = MF\) , let \(N\) denote the midpoint of \(\overline{AF}\) ; then \(\overline{MN}\) is a midline of the parallelogram, so \(\overline{MN} \perp \overline{AF}\) . \(\square\)

Since \(\overline{CM} \perp \overline{BC}\) and \(M\) is the center of \((AFP)\) , it follows \(CX = CY\) .

|

{

"resource_path": "USAMO/segmented/en-USAMO-2025-notes.jsonl",

"problem_match": "4. ",

"solution_match": "## \\(\\S 2.1\\) USAMO 2025/4, proposed by Carl Schildkraut \n"

}

|

2025

|

T1

|

5

| null |

USAMO

|

Find all positive integers \(k\) such that: for every positive integer \(n\) , the sum

\[\binom{n}{0}^{k} + \binom{n}{1}^{k} + \dots +\binom{n}{n}^{k}\]

is divisible by \(n + 1\) .

|

The answer is all even \(k\) .

Let's abbreviate \(S(n) := \binom{n}{0}^{k} + \dots + \binom{n}{n}^{k}\) for the sum in the problem.

\(\P\) Proof that even \(k\) is necessary. Choose \(n = 2\) . We need \(3 \mid S(2) = 2 + 2^{k}\) , which requires \(k\) to be even.

Remark. It's actually not much more difficult to just use \(n = p - 1\) for prime \(p\) , since \(\binom{p- 1}{i} \equiv (- 1)^{i} \pmod{p}\) . Hence \(S(p- 1) \equiv 1 + (- 1)^{k} + 1 + (- 1)^{k} + \dots + 1 \pmod{p}\) , and this also requires \(k\) to be even. This special case is instructive in figuring out the proof to follow.

\(\P\) Proof that \(k\) is sufficient. From now on we treat \(k\) as fixed, and we let \(p^{e}\) be a prime fully dividing \(n + 1\) . The basic idea is to reduce from \(n + 1\) to \((n + 1) / p\) by an induction.

Remark. Here is a concrete illustration that makes it clear what's going on. Let \(p = 5\) . When \(n = p - 1 = 4\) , we have

\[S(4) = 1^{k} + 4^{k} + 6^{k} + 4^{k} + 1^{k} \equiv 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 \equiv 0 \pmod{5}.\]

When \(n = p^{2} - 1 = 24\) , the 25 terms of \(S(24)\) in order are, modulo 25,

\[S(24)\equiv 1^{k}+1^{k}+1^{k}+1^{k}+1^{k}\] \[\qquad+4^{k}+4^{k}+4^{k}+4^{k}+4^{k}\] \[\qquad+6^{k}+6^{k}+6^{k}+6^{k}+6^{k}\] \[\qquad+4^{k}+4^{k}+4^{k}+4^{k}+4^{k}\] \[\qquad+1^{k}+1^{k}+1^{k}+1^{k}+1^{k}\] \[\qquad=5(1^{k}+4^{k}+6^{k}+4^{k}+1^{k}).\]

The point is that \(S(24)\) has five copies of \(S(4)\) , modulo 25.

To make the pattern in the remark explicit, we prove the following lemma on each individual binomial coefficient.

## Lemma 2.1

Suppose \(p^{e}\) is a prime power which fully divides \(n + 1\) . Then

\[\binom{n}{i}\equiv\pm\binom{\frac{n+1}{p}-1}{\lfloor i/p\rfloor}\pmod{p^{e}}.\]

Proof of lemma. It's easiest to understand the proof by looking at the cases \(\lfloor i / p\rfloor \in\) \(\{0,1,2\}\) first.

For \(0\leq i< p\) , since \(n\equiv - 1\) mod \(p^{e}\) , we have

\[\binom{n}{i}=\frac{n(n-1)\ldots(n-i+1)}{1\cdot2\cdot\cdots\cdot i}\equiv\frac{(-1)(-2)\ldots(-i)}{1\cdot2\cdot\cdots\cdot i}\equiv\pm 1\pmod{p^{e}}.\]

For \(p\leq i< 2p\) we have

\[\binom{n}{i}\equiv\pm 1\cdot\frac{n-p+1}{p}\cdot\frac{(n-p)(n-p-1)\ldots(n-i+1)}{(p+1)(p+2)\ldots i}\] \[\qquad\equiv\pm 1\cdot\frac{\frac{n-p+1}{p}\cdot\pm 1}{1}\] \[\qquad\equiv\pm\binom{\frac{n+1}{p}-1}{1}\pmod{p^{e}}.\]

For \(2p\leq i< 3p\) the analogous reasoning gives

\[\binom{n}{i}\equiv\pm 1\cdot\frac{n-p+1}{p}\cdot\pm 1\cdot\frac{n-2p+1}{2p}\cdot\pm 1\] \[\qquad\equiv\pm\frac{\binom{n+1}{p}-1}{1\cdot2}\binom{\frac{n+1}{p}-2}{2}\] \[\qquad\equiv\pm\binom{\frac{n+1}{p}-1}{2}\pmod{p^{e}}.\]

And so on. The point is that in general, if we write

\[\binom{n}{i}=\prod_{1\leq j\leq i}\frac{n-(j-1)}{j}\]

then the fractions for \(p\nmid j\) are all \(\pm 1\) (mod \(p^{e}\) ). So only considers those \(j\) with \(p\mid j\) ; in that case one obtains the claimed \(\binom{\frac{n+1}{p}-1}{\lfloor i/p\rfloor}\) exactly (even without having to take modulo \(p^{e}\) ). \(\square\)

From the lemma, it follows if \(p^{e}\) is a prime power which fully divides \(n + 1\) , then

\[S(n)\equiv p\cdot S\left(\frac{n + 1}{p} -1\right)\pmod{p^{e}}\]

by grouping the \(n + 1\) terms (for \(0\leq i\leq n\) ) into consecutive ranges of length \(p\) (by the value of \(\lfloor i / p\rfloor\) ).

Remark. Actually, with the exact same proof (with better \(\pm\) bookkeeping) one may show that

\[n + 1\mid \sum_{i = 0}^{n}\left((-1)^{i}\binom{n}{i}\right)^{k}\]

holds for all nonnegative integers \(k\) , not just \(k\) even. So in some sense this result is more natural than the one in the problem statement.

|

{

"resource_path": "USAMO/segmented/en-USAMO-2025-notes.jsonl",

"problem_match": "5. ",

"solution_match": "## \\(\\S 2.2\\) USAMO 2025/5, proposed by John Berman \n"

}

|

2025

|

T1

|

6

| null |

USAMO

|

Let \(m\) and \(n\) be positive integers with \(m \geq n\) . There are \(m\) cupcakes of different flavors arranged around a circle and \(n\) people who like cupcakes. Each person assigns a nonnegative real number score to each cupcake, depending on how much they like the cupcake. Suppose that for each person \(P\) , it is possible to partition the circle of \(m\) cupcakes into \(n\) groups of consecutive cupcakes so that the sum of \(P\) 's scores of the cupcakes in each group is at least 1. Prove that it is possible to distribute the \(m\) cupcakes to the \(n\) people so that each person \(P\) receives cupcakes of total score at least 1 with respect to \(P\) .

|

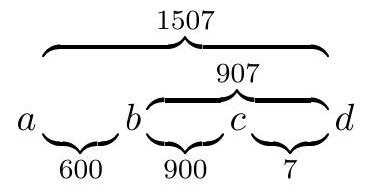

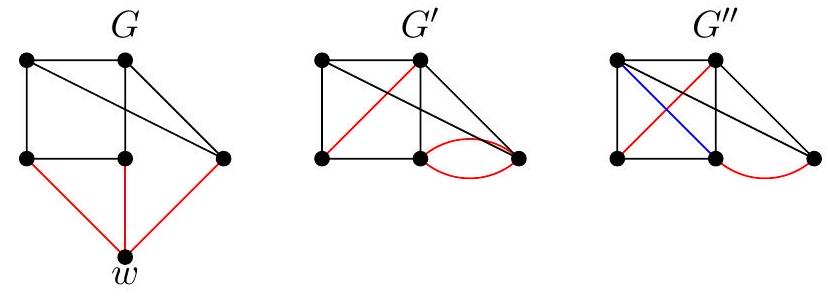

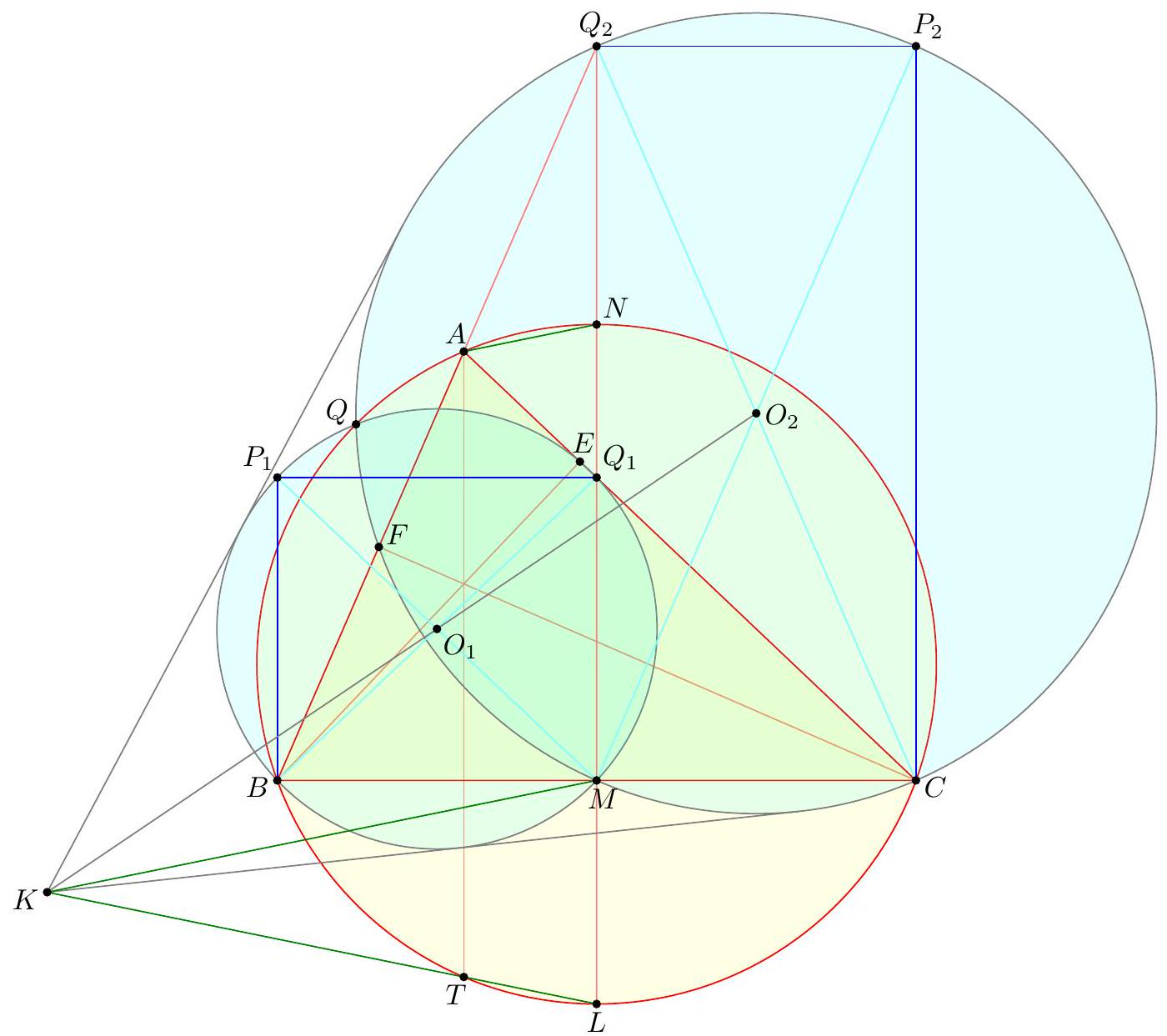

Arbitrarily pick any one person — call her Pip — and her \(n\) arcs. The initial idea is to try to apply Hall's marriage lemma to match the \(n\) people with Pip's arcs (such that each such person is happy with their matched arc). To that end, construct the obvious bipartite graph \(\mathfrak{G}\) between the people and the arcs for Pip.

We now consider the following algorithm, which takes several steps.

- If a perfect matching of \(\mathfrak{G}\) exists, we're done!- We're probably not that lucky. Per Hall's condition, this means there is a bad set \(B_{1}\) of people, who are compatible with fewer than \(|B_{1}|\) of the arcs. Then delete \(B_{1}\) and the neighbors of \(B_{1}\) , then try to find a matching on the remaining graph.- If a matching exists now, terminate the algorithm. Otherwise, that means there's another bad set \(B_{2}\) for the remaining graph. We again delete \(B_{2}\) and the fewer than \(B_{2}\) neighbors.- Repeat until some perfect matching \(\mathcal{M}\) is possible in the remaining graph, i.e. there are no more bad sets (and then terminate once that occurs). Since Pip is a universal vertex, it's impossible to delete Pip, so the algorithm does indeed terminate with nonempty \(\mathcal{M}\) .

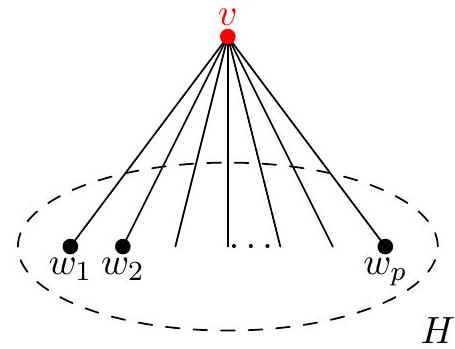

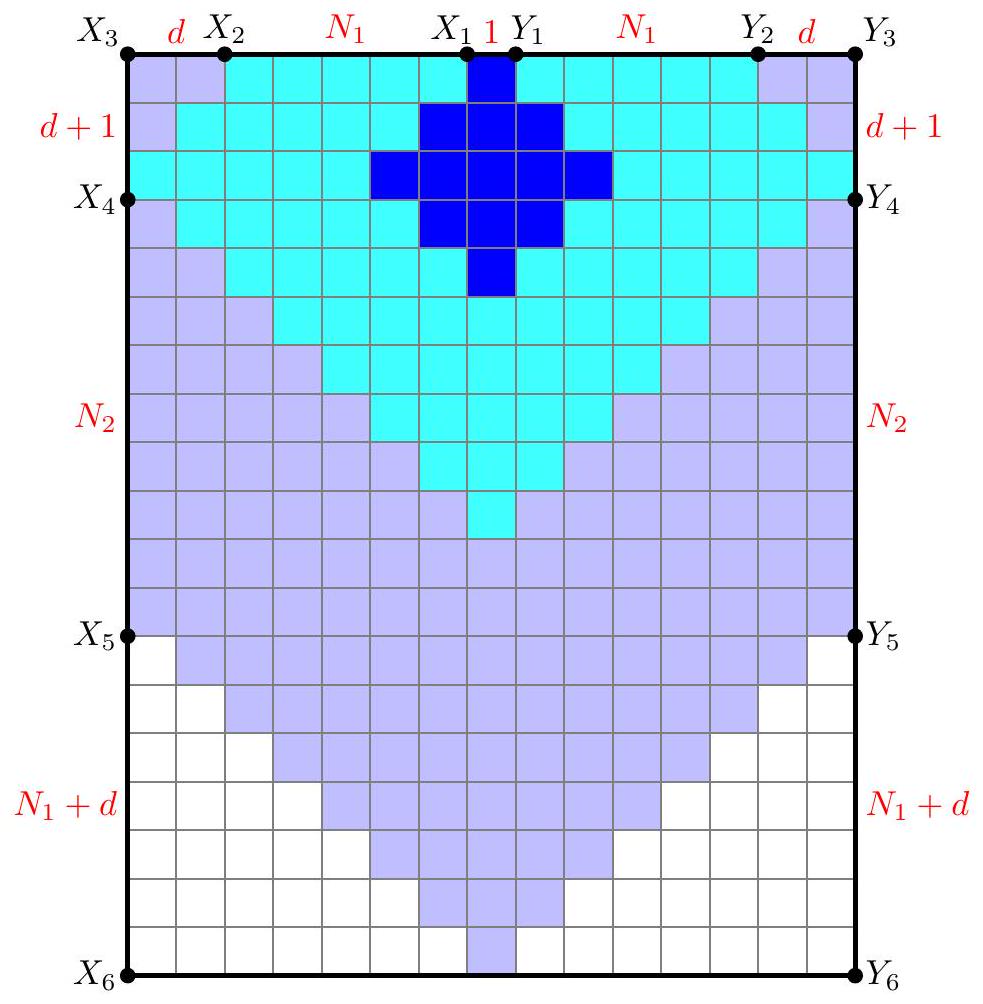

A cartoon of this picture is shown below.

We commit to assigning each of person in \(\mathcal{M}\) their matched arc (in particular if there are no bad sets at all, the problem is already solved). Now we finish the problem by induction on \(n\) (for the remaining people) by simply deleting the arcs used up by \(\mathcal{M}\) .

To see why this deletion- induction works, consider any particular person Quinn not in \(\mathcal{M}\) . By definition, Quinn is not happy with any of the arcs in \(\mathcal{M}\) . So when an arc \(\mathcal{A}\) of \(\mathcal{M}\) is deleted, it had value less than 1 for Quinn so in particular it couldn't contain entirely any of Quinn's arcs. Hence at most one endpoint among Quinn's arcs was in the deleted arc \(\mathcal{A}\) . When this happens, this causes two arcs of Quinn to merge, and the merged value is

\[(\geq 1) + (\geq 1) - (\leq 1)\qquad \geq \qquad 1\]

meaning the induction is OK. See below for a cartoon of the deletion, where Pip's arcs are drawn in blue while Quinn's arcs and scores are drawn in red (in this example \(n = 3\) ).

Remark. This deletion argument can be thought of in some special cases even before the realization of Hall, in the case where \(\mathcal{M}\) has only one person (Pip). This amounts to saying that if one of Pip's arcs isn't liked by anybody, then that arc can be deleted and the induction carries through.

Remark. Conversely, it should be reasonable to expect Hall's theorem to be helpful even before finding the deletion argument. While working on this problem, one of the first things I said was:

"We should let Hall do the heavy lifting for us: find a way to make \(n\) groups that satisfy Hall's condition, rather than an assignment of \(n\) groups to \(n\) people."

As a general heuristic, for any type of "compatible matching" problem, Hall's condition is usually the go- to tool. (It is much easier to verify Hall's condition than actually find the matching yourself.) Actually in most competition problems, if one realizes one is in a Hall setting, one is usually close to finishing the problem. This is a relatively rare example in which one needs an additional idea to go alongside Hall's theorem.

|

{

"resource_path": "USAMO/segmented/en-USAMO-2025-notes.jsonl",

"problem_match": "6. ",

"solution_match": "## \\(\\S 2.3\\) USAMO 2025/6, proposed by Cheng-Yin Chang and Hung-Hsun Yu \n"

}

|

2014

|

T0

|

1

| null |

USA_TST

|

Let $A B C$ be an acute triangle, and let $X$ be a variable interior point on the minor $\operatorname{arc} B C$ of its circumcircle. Let $P$ and $Q$ be the feet of the perpendiculars from $X$ to lines $C A$ and $C B$, respectively. Let $R$ be the intersection of line $P Q$ and the perpendicular from $B$ to $A C$. Let $\ell$ be the line through $P$ parallel to $X R$. Prove that as $X$ varies along minor arc $B C$, the line $\ell$ always passes through a fixed point.

|

The fixed point is the orthocenter, since $\ell$ is a Simson line. See Lemma 4.4 of Euclidean Geometry in Math Olympiads.

|

{

"resource_path": "USA_TST/segmented/en-sols-TST-IMO-2014.jsonl",

"problem_match": null,

"solution_match": null

}

|

2014

|

T0

|

2

| null |

USA_TST

|

Let $a_{1}, a_{2}, a_{3}, \ldots$ be a sequence of integers, with the property that every consecutive group of $a_{i}$ 's averages to a perfect square. More precisely, for all positive integers $n$ and $k$, the quantity $$ \frac{a_{n}+a_{n+1}+\cdots+a_{n+k-1}}{k} $$ is always the square of an integer. Prove that the sequence must be constant (all $a_{i}$ are equal to the same perfect square).

|

Let $\nu_{p}(n)$ denote the largest exponent of $p$ dividing $n$. The problem follows from the following proposition. ## Proposition Let $\left(a_{n}\right)$ be a sequence of integers and let $p$ be a prime. Suppose that every consecutive group of $a_{i}$ 's with length at most $p$ averages to a perfect square. Then $\nu_{p}\left(a_{i}\right)$ is independent of $i$. We proceed by induction on the smallest value of $\nu_{p}\left(a_{i}\right)$ as $i$ ranges (which must be even, as each of the $a_{i}$ are themselves a square). First we prove two claims. Claim - If $j \equiv k(\bmod p)$ then $a_{j} \equiv a_{k}(\bmod p)$. Claim - If some $a_{i}$ is divisible by $p$ then all of them are. $$ S_{n}=a_{1}+a_{2}+\cdots+a_{n} \equiv a_{2}+\cdots+a_{n} \quad(\bmod p) $$ Call an integer $k$ with $2 \leq k<p$ a pivot if $1-k^{-1}$ is a quadratic nonresidue modulo $p$. We claim that for any pivot $k, S_{k} \equiv 0(\bmod p)$. If not, then $$ \frac{a_{1}+a_{2}+\cdots+a_{k}}{k} \text { and } \frac{a_{2}+\cdots+a_{k}}{k-1} $$ are both qudaratic residues. Division implies that $\frac{k-1}{k}=1-k^{-1}$ is a quadratic residue, contradiction. Next we claim that there is an integer $m$ with $S_{m} \equiv S_{m+1} \equiv 0(\bmod p)$, which implies $p \mid a_{m+1}$. If 2 is a pivot, then we simply take $m=1$. Otherwise, there are $\frac{1}{2}(p-1)$ pivots, one for each nonresidue (which includes neither 0 nor 1 ), and all pivots lie in [3, $p-1]$, so we can find an $m$ such that $m$ and $m+1$ are both pivots. Repeating this procedure starting with $a_{m+1}$ shows that $a_{2 m+1}, a_{3 m+1}, \ldots$ must all be divisible by $p$. Combined with the first claim and the fact that $m<p$, we find that all the $a_{i}$ are divisible by $p$. The second claim establishes the base case of our induction. Now assume all $a_{i}$ are divisible by $p$ and hence $p^{2}$. Then all the averages in our proposition (with length at $\operatorname{most} p$ ) are divisible by $p$ and hence $p^{2}$. Thus the map $a_{i} \mapsto \frac{1}{p^{2}} a_{i}$ gives a new sequence satisfying the proposition, and our inductive hypothesis completes the proof. Remark. There is a subtle bug that arises if one omits the condition that $k \leq p$ in the proposition. When $k=p^{2}$ the average $\frac{a_{1}+\cdots+a_{p^{2}}}{p^{2}}$ is not necessarily divisible by $p$ even if all the $a_{i}$ are. Hence it is not valid to divide through by $p$. This is why the condition $k \leq p$ was added.

|

{

"resource_path": "USA_TST/segmented/en-sols-TST-IMO-2014.jsonl",

"problem_match": null,

"solution_match": null

}

|

2014

|

T0

|

3

| null |

USA_TST

|

Let $n$ be an even positive integer, and let $G$ be an $n$-vertex (simple) graph with exactly $\frac{n^{2}}{4}$ edges. An unordered pair of distinct vertices $\{x, y\}$ is said to be amicable if they have a common neighbor (there is a vertex $z$ such that $x z$ and $y z$ are both edges). Prove that $G$ has at least $2\binom{n / 2}{2}$ pairs of vertices which are amicable.

|

First, we prove the following lemma. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Friendship_ paradox). Lemma (On average, your friends are more popular than you) For a vertex $v$, let $a(v)$ denote the average degree of the neighbors of $v$ (setting $a(v)=0$ if $\operatorname{deg} v=0)$. Then $$ \sum_{v} a(v) \geq \sum_{v} \operatorname{deg} v=2 \# E $$ $$ \begin{aligned} \sum_{v} a(v) & =\sum_{v} \frac{\sum_{w \sim v} \operatorname{deg} w}{\operatorname{deg} v} \\ & =\sum_{v} \sum_{w \sim v} \frac{\operatorname{deg} w}{\operatorname{deg} v} \\ & =\sum_{\text {edges } v w}\left(\frac{\operatorname{deg} w}{\operatorname{deg} v}+\frac{\operatorname{deg} v}{\operatorname{deg} w}\right) \\ & \stackrel{\text { AM-GM }}{\geq} \sum_{\text {edges } v w} 2=2 \# E=\sum_{v} \operatorname{deg} v \end{aligned} $$ as desired. Corollary (On average, your most popular friend is more popular than you) For a vertex $v$, let $m(v)$ denote the maximum degree of the neighbors of $v$ (setting $m(v)=0$ if $\operatorname{deg} v=0)$. Then $$ \sum_{v} m(v) \geq \sum_{v} \operatorname{deg} v=2 \# E \text {. } $$ We can use this to count amicable pairs by noting that any particular vertex $v$ is in at least $m(v)-1$ amicable pairs. So, the number of amicable pairs is at least $$ \frac{1}{2} \sum_{v}(m(v)-1) \geq \# E-\frac{1}{2} \# V $$ Note that up until now we haven't used any information about $G$. But now if we plug in $\# E=n^{2} / 4, \# V=n$, then we get exactly the desired answer. (Equality holds for $G=K_{n / 2, n / 2}$.)

|

{

"resource_path": "USA_TST/segmented/en-sols-TST-IMO-2014.jsonl",

"problem_match": null,

"solution_match": null

}

|

2014

|

T0

|

4

| null |

USA_TST

|

Let $n$ be a positive even integer, and let $c_{1}, c_{2}, \ldots, c_{n-1}$ be real numbers satisfying $$ \sum_{i=1}^{n-1}\left|c_{i}-1\right|<1 $$ Prove that $$ 2 x^{n}-c_{n-1} x^{n-1}+c_{n-2} x^{n-2}-\cdots-c_{1} x^{1}+2 $$ has no real roots.

|

We will prove the polynomial is positive for all $x \in \mathbb{R}$. As $c_{i}>0$, the result is vacuous for $x \leq 0$, so we restrict attention to $x>0$. Then letting $c_{i}=1-d_{i}$ for each $i$, the inequality we want to prove becomes $$ x^{n}+1+\frac{x^{n+1}+1}{x+1}>\sum_{1}^{n-1} d_{i} x^{i} \quad \text { given } \sum\left|d_{i}\right|<1 $$ But obviously $x^{n}+1>x^{i}$ for any $1 \leq i \leq n-1$ and $x>0$. So in fact $x^{n}+1>\sum_{1}^{n-1}\left|d_{i}\right| x^{i}$ holds for $x>0$, as needed.

|

{

"resource_path": "USA_TST/segmented/en-sols-TST-IMO-2014.jsonl",

"problem_match": null,

"solution_match": null

}

|

2014

|

T0

|

5

| null |

USA_TST

|

Let $A B C D$ be a cyclic quadrilateral, and let $E, F, G$, and $H$ be the midpoints of $A B, B C, C D$, and $D A$ respectively. Let $W, X, Y$ and $Z$ be the orthocenters of triangles $A H E, B E F, C F G$ and $D G H$, respectively. Prove that the quadrilaterals $A B C D$ and $W X Y Z$ have the same area.

|

We begin with: Claim - Point $W$ has coordinates $\frac{1}{2}(2 a+b+d)$. By symmetry, we have $$ \begin{aligned} w & =\frac{1}{2}(2 a+b+d) \\ x & =\frac{1}{2}(2 b+c+a) \\ y & =\frac{1}{2}(2 c+d+b) \\ z & =\frac{1}{2}(2 d+a+c) . \end{aligned} $$ We see that $w-y=a-c, x-z=b-d$. So the diagonals of $W X Y Z$ have the same length as those of $A B C D$ as well as the same directed angle between them. This implies the areas are equal, too.

|

{

"resource_path": "USA_TST/segmented/en-sols-TST-IMO-2014.jsonl",

"problem_match": null,

"solution_match": null

}

|

2014

|

T0

|

6

| null |

USA_TST

|

For a prime $p$, a subset $S$ of residues modulo $p$ is called a sum-free multiplicative subgroup of $\mathbb{F}_{p}$ if - there is a nonzero residue $\alpha$ modulo $p$ such that $S=\left\{1, \alpha^{1}, \alpha^{2}, \ldots\right\}$ (all considered $\bmod p$ ), and - there are no $a, b, c \in S$ (not necessarily distinct) such that $a+b \equiv c(\bmod p)$. Prove that for every integer $N$, there is a prime $p$ and a sum-free multiplicative subgroup $S$ of $\mathbb{F}_{p}$ such that $|S| \geq N$.

|

We first prove the following general lemma. ## Lemma If $f, g \in \mathbb{Z}[X]$ are relatively prime nonconstant polynomials, then for sufficiently large primes $p$, they have no common root modulo $p$. $$ a(X) f(X)+b(X) g(X) \equiv c $$ So, plugging in $X=r$ we get $p \mid c$, so the set of permissible primes $p$ is finite. With this we can give the construction. ## Claim - Suppose that - $n$ is a positive integer with $n \not \equiv 0(\bmod 3)$; - $p$ is a prime which is $1 \bmod n$; and - $\alpha$ is a primitive $n^{\prime}$ th root of unity modulo $p$. Then $|S|=n$ and, if $p$ is sufficiently large in $n$, is also sum-free. $$ 1+\alpha^{k} \equiv \alpha^{m} \quad(\bmod p) $$ for some integers $k, m \in \mathbb{Z}$. This means $(X+1)^{n}-1$ and $X^{n}-1$ have common root $X=\alpha^{k}$. But $$ \underset{\mathbb{Z}[x]}{\operatorname{gcd}}\left((X+1)^{n}-1, X^{n}-1\right)=1 \quad \forall n \not \equiv 0 \quad(\bmod 3) $$ because when $3 \nmid n$ the two polynomials have no common complex roots. (Indeed, if $|\omega|=|1+\omega|=1$ then $\omega=-\frac{1}{2} \pm \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} i$.) Thus $p$ is bounded by the lemma, as desired.

|

{

"resource_path": "USA_TST/segmented/en-sols-TST-IMO-2014.jsonl",

"problem_match": null,

"solution_match": null

}

|

2015

|

T0

|

1

| null |

USA_TST

|

Let $A B C$ be a scalene triangle with incenter $I$ whose incircle is tangent to $\overline{B C}$, $\overline{C A}, \overline{A B}$ at $D, E, F$, respectively. Denote by $M$ the midpoint of $\overline{B C}$ and let $P$ be a point in the interior of $\triangle A B C$ so that $M D=M P$ and $\angle P A B=\angle P A C$. Let $Q$ be a point on the incircle such that $\angle A Q D=90^{\circ}$. Prove that either $\angle P Q E=90^{\circ}$ or $\angle P Q F=90^{\circ}$.

|

First, we claim that $D, P, E$ are collinear. Let $N$ be the midpoint of $\overline{A B}$. It is well-known that the three lines $M N, D E, A I$ are concurrent at a point (see for example problem 6 of USAJMO 2014). Let $P^{\prime}$ be this intersection point, noting that $P^{\prime}$ actually lies on segment $D E$. Then $P^{\prime}$ lies inside $\triangle A B C$ and moreover $$ \triangle D P^{\prime} M \sim \triangle D E C $$ so $M P^{\prime}=M D$. Hence $P^{\prime}=P$, proving the claim. Let $S$ be the point diametrically opposite $D$ on the incircle, which is also the second intersection of $\overline{A Q}$ with the incircle. Let $T=\overline{A Q} \cap \overline{B C}$. Then $T$ is the contact point of the $A$-excircle; consequently, $$ M D=M P=M T $$ and we obtain a circle with diameter $\overline{D T}$. Since $\angle D Q T=\angle D Q S=90^{\circ}$ we have $Q$ on this circle as well. As $\overline{S D}$ is tangent to the circle with diameter $\overline{D T}$, we obtain $$ \angle P Q D=\angle S D P=\angle S D E=\angle S Q E . $$ Since $\angle D Q S=90^{\circ}, \angle P Q E=90^{\circ}$ too. 【 Solution using spiral similarity. We will ignore for now the point $P$. As before define $S, T$ and note $\overline{A Q S T}$ collinear, as well as $D P Q T$ cyclic on circle $\omega$ with diameter $\overline{D T}$. Let $\tau$ be the spiral similarity at $Q$ sending $\omega$ to the incircle. We have $\tau(T)=D$, $\tau(D)=S, \tau(Q)=Q$. Now $$ I=\overline{D D} \cap \overline{Q Q} \Longrightarrow \tau(I)=\overline{S S} \cap \overline{Q Q} $$ and hence we conclude $\tau(I)$ is the pole of $\overline{A S Q T}$ with respect to the incircle, which lies on line $E F$. Then since $\overline{A I} \perp \overline{E F}$ too, we deduce $\tau$ sends line $A I$ to line $E F$, hence $\tau(P)$ must be either $E$ or $F$ as desired. 【 Authorship comments. Written April 2014. I found this problem while playing with GeoGebra. Specifically, I started by drawing in the points $A, B, C, I, D, M, T$, common points. I decided to add in the circle with diameter $D T$, because of the synergy it had with the rest of the picture. After a while of playing around, I intersected ray $A I$ with the circle to get $P$, and was surprised to find that $D, P, E$ were collinear, which I thought was impossible since the setup should have been symmetric. On further reflection, I realized it was because $A I$ intersected the circle twice, and set about trying to prove this. I noticed the relation $\angle P Q E=90^{\circ}$ in my attempts to prove the result, even though this ended up being a corollary rather than a useful lemma.

|

{

"resource_path": "USA_TST/segmented/en-sols-TST-IMO-2015.jsonl",

"problem_match": null,

"solution_match": null

}

|

2015

|

T0

|

2

| null |

USA_TST

|

Prove that for every positive integer $n$, there exists a set $S$ of $n$ positive integers such that for any two distinct $a, b \in S, a-b$ divides $a$ and $b$ but none of the other elements of $S$.

|

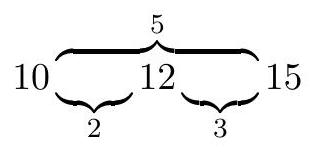

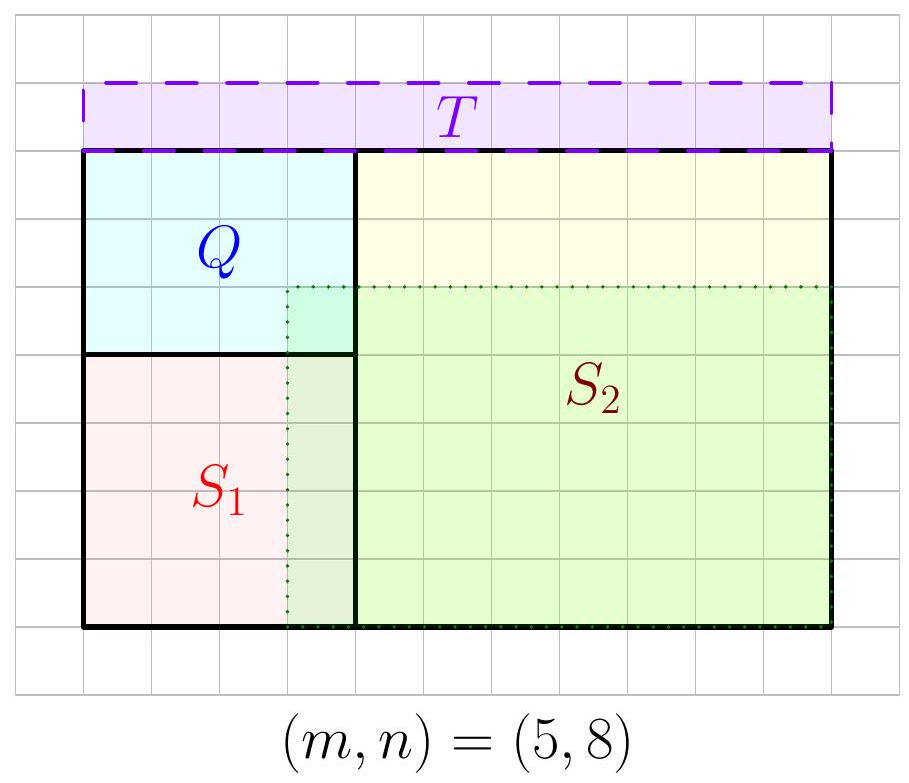

The idea is to look for a sequence $d_{1}, \ldots, d_{n-1}$ of "differences" such that the following two conditions hold. Let $s_{i}=d_{1}+\cdots+d_{i-1}$, and $t_{i, j}=d_{i}+\cdots+d_{j-1}$ for $i \leq j$. (i) No two of the $t_{i, j}$ divide each other. (ii) There exists an integer $a$ satisfying the CRT equivalences $$ a \equiv-s_{i} \quad\left(\bmod t_{i, j}\right) \quad \forall i \leq j $$ Then the sequence $a+s_{1}, a+s_{2}, \ldots, a+s_{n}$ will work. For example, when $n=3$ we can take $\left(d_{1}, d_{2}\right)=(2,3)$ giving  because the only conditions we need satisfy are $$ \begin{aligned} a & \equiv 0 \quad(\bmod 2) \\ a & \equiv 0 \quad(\bmod 5) \\ a & \equiv-2 \quad(\bmod 3) . \end{aligned} $$ But with this setup we can just construct the $d_{i}$ inductively. To go from $n$ to $n+1$, take a $d_{1}, \ldots, d_{n-1}$ and let $p$ be a prime not dividing any of the $d_{i}$. Moreover, let $M$ be a multiple of $\prod_{i \leq j} t_{i, j}$ coprime to $p$. Then we claim that $d_{1} M, d_{2} M, \ldots, d_{n-1} M, p$ is such a difference sequence. For example, the previous example extends as follows with $M=300$ and $p=7$.  The new numbers $p, p+M t_{n-1, n}, p+M t_{n-2, n}, \ldots$ are all relatively prime to everything else. Hence (i) still holds. To see that (ii) still holds, just note that we can still get a family of solutions for the first $n$ terms, and then the last $(n+1)$ st term can be made to work by Chinese Remainder Theorem since all the new $p+M t_{n-2, n}$ are coprime to everything.

|

{

"resource_path": "USA_TST/segmented/en-sols-TST-IMO-2015.jsonl",

"problem_match": null,

"solution_match": null

}

|

2015

|

T0

|

3

| null |

USA_TST

|

A physicist encounters 2015 atoms called usamons. Each usamon either has one electron or zero electrons, and the physicist can't tell the difference. The physicist's only tool is a diode. The physicist may connect the diode from any usamon $A$ to any other usamon $B$. (This connection is directed.) When she does so, if usamon $A$ has an electron and usamon $B$ does not, then the electron jumps from $A$ to $B$. In any other case, nothing happens. In addition, the physicist cannot tell whether an electron jumps during any given step. The physicist's goal is to isolate two usamons that she is $100 \%$ sure are currently in the same state. Is there any series of diode usage that makes this possible?

|

The answer is no. Call the usamons $U_{1}, \ldots, U_{m}$ (here $m=2015$ ). Consider models $M_{k}$ of the following form: $U_{1}, \ldots, U_{k}$ are all charged for some $0 \leq k \leq m$ and the other usamons are not charged. Note that for any pair there's a model where they are different states, by construction. We can consider the physicist as acting on these $m+1$ models simultaneously, and trying to reach a state where there's a pair in all models which are all the same charge. (This is a necessary condition for a winning strategy to exist.) But we claim that any diode operation $U_{i} \rightarrow U_{j}$ results in the $m+1$ models being an isomorphic copy of the previous set. If $i<j$ then the diode operation can be interpreted as just swapping $U_{i}$ with $U_{j}$, which doesn't change anything. Moreover if $i>j$ the operation never does anything. The conclusion follows from this. Remark. This problem is not a "standard" olympiad problem, so I can't say it's trivial. But the idea is pretty natural I think. You can motivate it as follows: there's a sequence of diode operations you can do which forces the situation to be one of the $M_{k}$ above: first, use the diode into $U_{1}$ for all other $U_{i}$ 's, so that either no electrons exist at all or $U_{1}$ has an electron. Repeat with the other $U_{i}$. This leaves us at the situation described at the start of the problem. Then you could guess the answer was "no" just based on the fact that it's impossible for $n=2,3$ and that there doesn't seem to be a reasonable strategy. In this way it's possible to give a pretty good description of what it's possible to do. One possible phrasing: "the physicist can arrange the usamons in a line such that all the charged usamons are to the left of the un-charged usamons, but can't determine the number of charged usamons".

|

{

"resource_path": "USA_TST/segmented/en-sols-TST-IMO-2015.jsonl",

"problem_match": null,

"solution_match": null

}

|

2015

|

T0

|

4

| null |

USA_TST

|

Let $f: \mathbb{Q} \rightarrow \mathbb{Q}$ be a function such that for any $x, y \in \mathbb{Q}$, the number $f(x+y)-$ $f(x)-f(y)$ is an integer. Decide whether there must exist a constant $c$ such that $f(x)-c x$ is an integer for every rational number $x$.

|

No, such a constant need not exist. $$ \begin{aligned} & 2 x_{1}=x_{0} \\ & 2 x_{2}=x_{1}+1 \\ & 2 x_{3}=x_{2} \\ & 2 x_{4}=x_{3}+1 \\ & 2 x_{5}=x_{4} \\ & 2 x_{6}=x_{5}+1 \end{aligned} $$ Set $f\left(2^{-k}\right)=x_{k}$ and $f\left(2^{k}\right)=2^{k}$ for $k=0,1, \ldots$ Then, let $$ f\left(a \cdot 2^{k}+\frac{b}{c}\right)=a f\left(2^{k}\right)+\frac{b}{c} $$ for odd integers $a, b, c$. One can verify this works. $$ f\left(\frac{p}{q}\right)=\frac{p}{q}(1!+2!+\cdots+q!) . $$ Remark. Silly note: despite appearances, $f(x)=\lfloor x\rfloor$ is not a counterexample since one can take $c=0$.

|

{

"resource_path": "USA_TST/segmented/en-sols-TST-IMO-2015.jsonl",

"problem_match": null,

"solution_match": null

}

|

2015

|

T0

|

5

| null |

USA_TST

|

Fix a positive integer $n$. A tournament on $n$ vertices has all its edges colored by $\chi$ colors, so that any two directed edges $u \rightarrow v$ and $v \rightarrow w$ have different colors. Over all possible tournaments on $n$ vertices, determine the minimum possible value of $\chi$.

|

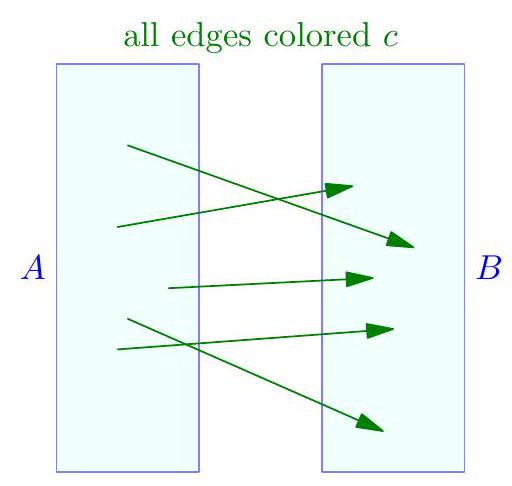

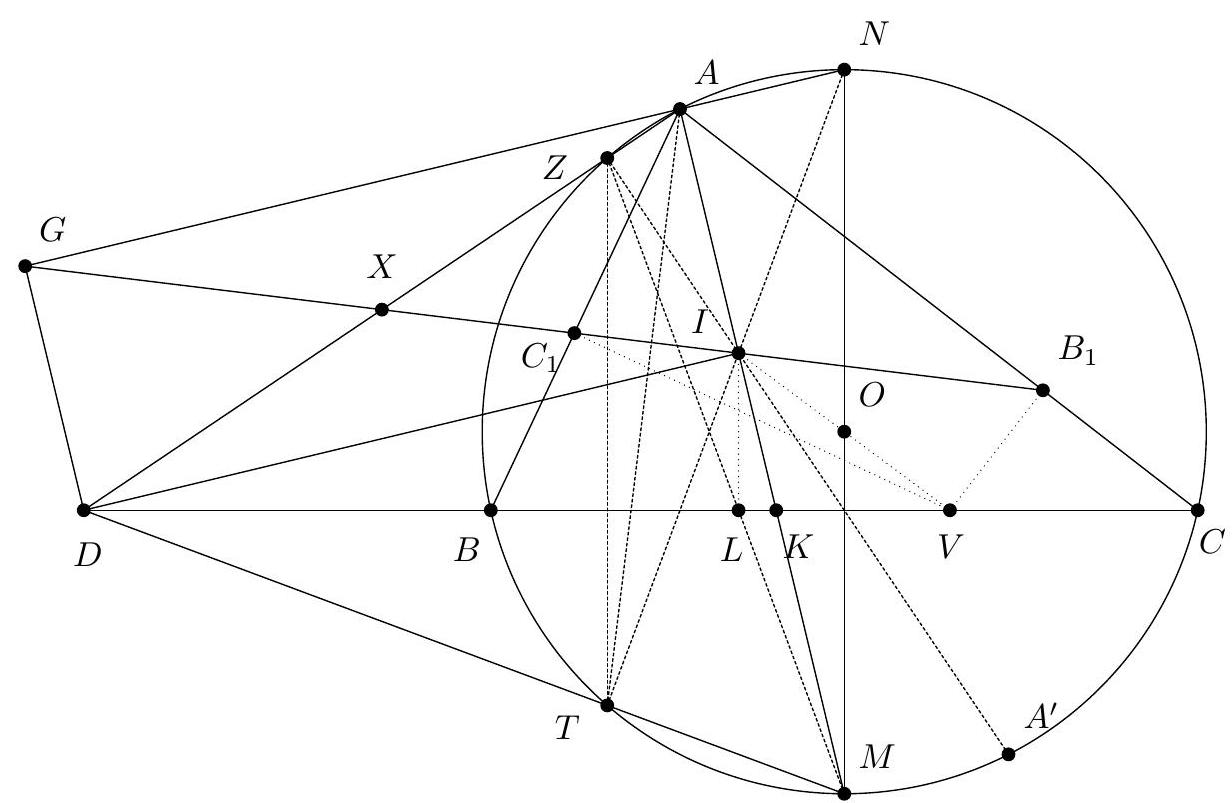

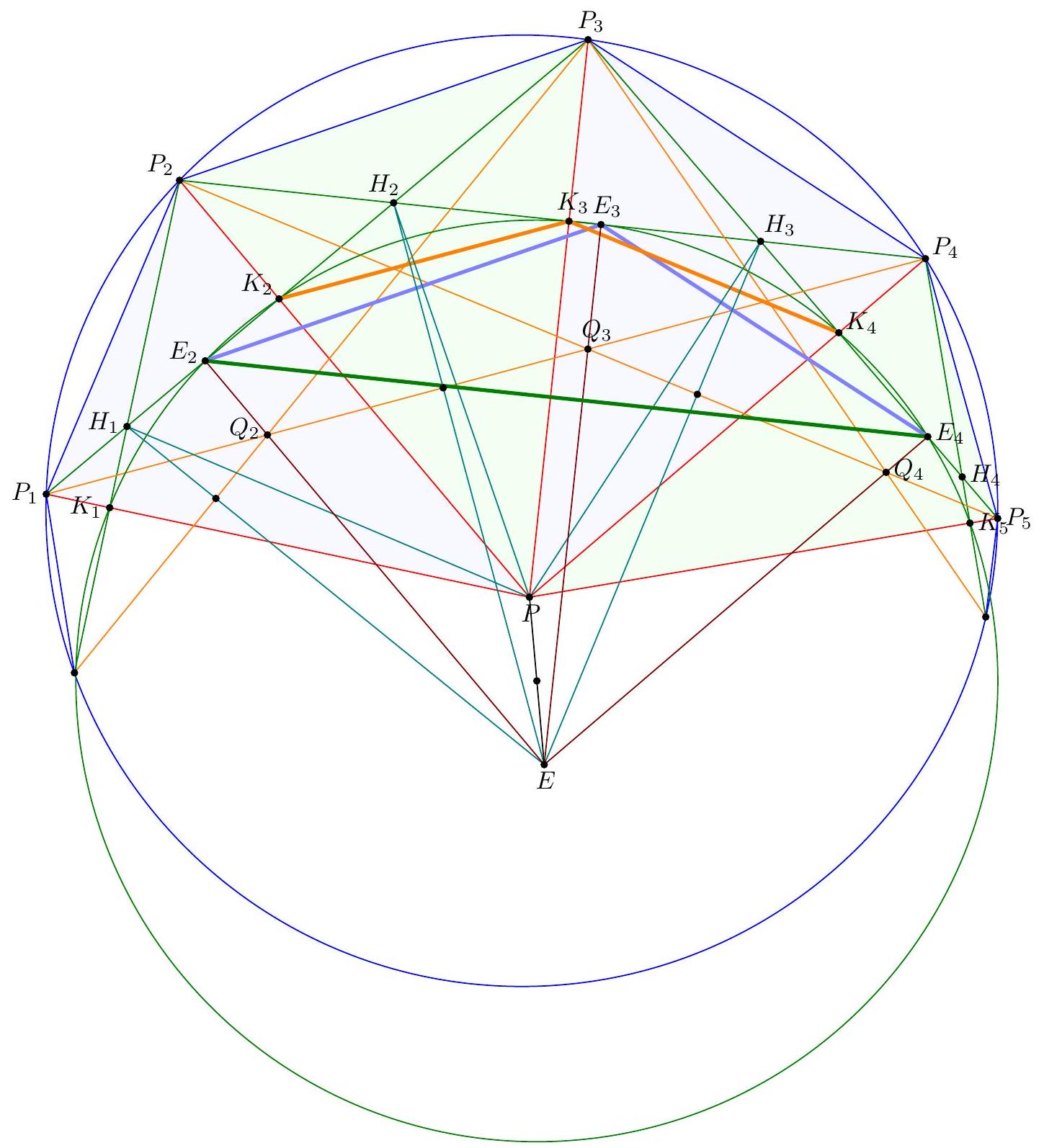

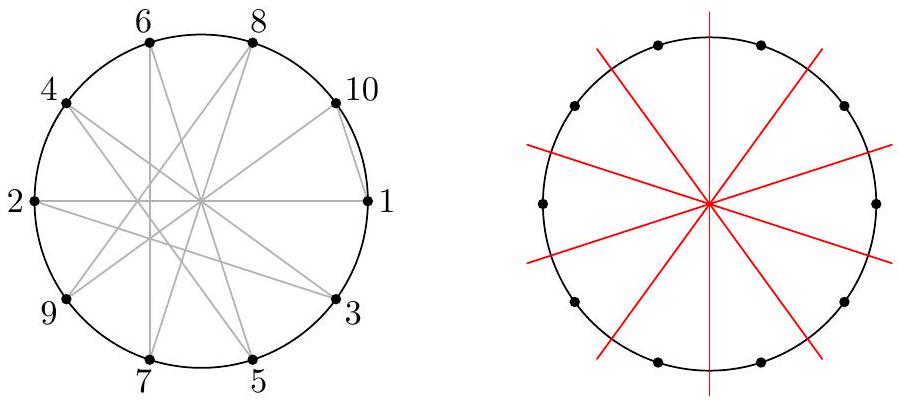

The answer is $$ \chi=\left\lceil\log _{2} n\right\rceil $$ First, we prove by induction on $n$ that $\chi \geq \log _{2} n$ for any coloring and any tournament. The base case $n=1$ is obvious. Now given any tournament, consider any used color $c$. Then it should be possible to divide the tournament into two subsets $A$ and $B$ such that all $c$-colored edges point from $A$ to $B$ (for example by letting $A$ be all vertices which are the starting point of a $c$-edge).  One of $A$ and $B$ has size at least $n / 2$, say $A$. Since $A$ has no $c$ edges, and uses at least $\log _{2}|A|$ colors other than $c$, we get $$ \chi \geq 1+\log _{2}(n / 2)=\log _{2} n $$ completing the induction. One can read the construction off from the argument above, but here is a concrete description. For each integer $n$, consider the tournament whose vertices are the binary representations of $S=\{0, \ldots, n-1\}$. Instantiate colors $c_{1}, c_{2}, \ldots$. Then for $v, w \in S$, we look at the smallest order bit for which they differ; say the $k$ th one. If $v$ has a zero in the $k$ th bit, and $w$ has a one in the $k$ th bit, we draw $v \rightarrow w$. Moreover we color the edge with color $c_{k}$. This works and uses at most $\left\lceil\log _{2} n\right\rceil$ colors. Remark (Motivation). The philosophy "combinatorial optimization" applies here. The idea is given any color $c$, we can find sets $A$ and $B$ such that all $c$-edges point $A$ to $B$. Once you realize this, the next insight is to realize that you may as well color all the edges from $A$ to $B$ by $c$; after all, this doesn't hurt the condition and makes your life easier. Hence, if $f$ is the answer, we have already a proof that $f(n)=1+\max (f(|A|), f(|B|))$ and we choose $|A| \approx|B|$. This optimization also gives the inductive construction.

|

{

"resource_path": "USA_TST/segmented/en-sols-TST-IMO-2015.jsonl",

"problem_match": null,

"solution_match": null

}

|

2015

|

T0

|

6

| null |

USA_TST

|

Let $A B C$ be a non-equilateral triangle and let $M_{a}, M_{b}, M_{c}$ be the midpoints of the sides $B C, C A, A B$, respectively. Let $S$ be a point lying on the Euler line. Denote by $X, Y, Z$ the second intersections of $M_{a} S, M_{b} S, M_{c} S$ with the nine-point circle. Prove that $A X, B Y, C Z$ are concurrent.

|

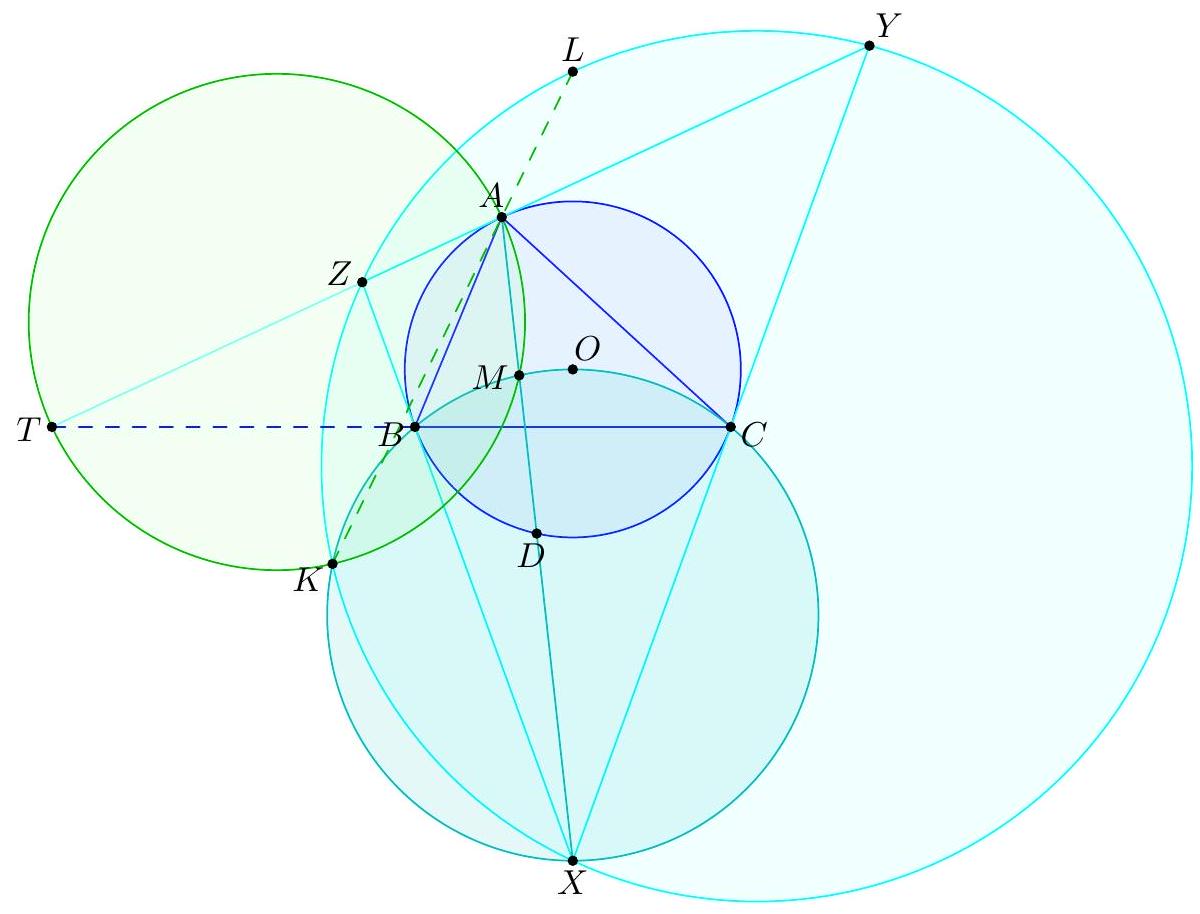

We assume now and forever that $A B C$ is scalene since the problem follows by symmetry in the isosceles case. We present four solutions. 【 First solution by barycentric coordinates (Evan Chen). Let $A X$ meet $M_{b} M_{c}$ at $D$, and let $X$ reflected over $M_{b} M_{c}^{\prime}$ 's midpoint be $X^{\prime}$. Let $Y^{\prime}, Z^{\prime}, E, F$ be similarly defined.  By Cevian Nest Theorem it suffices to prove that $M_{a} D, M_{b} E, M_{c} F$ are concurrent. Taking the isotomic conjugate and recalling that $M_{a} M_{b} A M_{c}$ is a parallelogram, we see that it suffices to prove $M_{a} X^{\prime}, M_{b} Y^{\prime}, M_{c} Z^{\prime}$ are concurrent. We now use barycentric coordinates on $\triangle M_{a} M_{b} M_{c}$. Let $$ S=\left(a^{2} S_{A}+t: b^{2} S_{B}+t: c^{2} S_{C}+t\right) $$ (possibly $t=\infty$ if $S$ is the centroid). Let $v=b^{2} S_{B}+t, w=c^{2} S_{C}+t$. Hence $$ X=\left(-a^{2} v w:\left(b^{2} w+c^{2} v\right) v:\left(b^{2} w+c^{2} v\right) w\right) $$ Consequently, $$ X^{\prime}=\left(a^{2} v w:-a^{2} v w+\left(b^{2} w+c^{2} v\right) w:-a^{2} v w+\left(b^{2} w+c^{2} v\right) v\right) $$ We can compute $$ b^{2} w+c^{2} v=(b c)^{2}\left(S_{B}+S_{C}\right)+\left(b^{2}+c^{2}\right) t=(a b c)^{2}+\left(b^{2}+c^{2}\right) t $$ Thus $$ -a^{2} v+b^{2} w+c^{2} v=\left(b^{2}+c^{2}\right) t+(a b c)^{2}-(a b)^{2} S_{B}-a^{2} t=S_{A}\left((a b)^{2}+t\right) $$ Finally $$ X^{\prime}=\left(a^{2} v w: S_{A}\left(c^{2} S_{C}+t\right)\left((a b)^{2}+2 t\right): S_{A}\left(b^{2} S_{B}+t\right)\left((a c)^{2}+2 t\right)\right) $$ and from this it's evident that $A X^{\prime}, B Y^{\prime}, C Z^{\prime}$ are concurrent.

|

{

"resource_path": "USA_TST/segmented/en-sols-TST-IMO-2015.jsonl",

"problem_match": null,

"solution_match": null

}

|

2015

|

T0

|

6

| null |

USA_TST

|

Let $A B C$ be a non-equilateral triangle and let $M_{a}, M_{b}, M_{c}$ be the midpoints of the sides $B C, C A, A B$, respectively. Let $S$ be a point lying on the Euler line. Denote by $X, Y, Z$ the second intersections of $M_{a} S, M_{b} S, M_{c} S$ with the nine-point circle. Prove that $A X, B Y, C Z$ are concurrent.

|

We assume now and forever that $A B C$ is scalene since the problem follows by symmetry in the isosceles case. We present four solutions. \ Second solution by moving points (Anant Mudgal). Let $H_{a}, H_{b}, H_{c}$ be feet of altitudes, and let $\gamma$ denote the nine-point circle. The main claim is that: Claim - Lines $X H_{a}, Y H_{b}, Z H_{c}$ are concurrent, $$ \begin{aligned} & \ell \rightarrow \gamma \rightarrow \ell \\ & S \mapsto X \mapsto S_{a}:=\ell \cap \overline{H_{a} X} \end{aligned} $$ is projective, because it consists of two perspectivities. So we want the analogous maps $S \mapsto S_{b}, S \mapsto S_{c}$ to coincide. For this it suffices to check three positions of $S$; since you're such a good customer here are four. - If $S$ is the orthocenter of $\triangle M_{a} M_{b} M_{c}$ (equivalently the circumcenter of $\triangle A B C$ ) then $S_{a}$ coincides with the circumcenter of $M_{a} M_{b} M_{c}$ (equivalently the nine-point center of $\triangle A B C)$. By symmetry $S_{b}$ and $S_{c}$ are too. - If $S$ is the circumcenter of $\triangle M_{a} M_{b} M_{c}$ (equivalently the nine-point center of $\triangle A B C$ ) then $S_{a}$ coincides with the de Longchamps point of $\triangle M_{a} M_{b} M_{c}$ (equivalently orthocenter of $\triangle A B C)$. By symmetry $S_{b}$ and $S_{c}$ are too. - If $S$ is either of the intersections of the Euler line with $\gamma$, then $S=S_{a}=S_{b}=S_{c}$ (as $S=X=Y=Z$ ).  We now use Trig Ceva to carry over the concurrence. By sine law, $$ \frac{\sin \angle M_{c} A X}{\sin \angle A M_{c} X}=\frac{M_{c} X}{A X} $$ and a similar relation for $M_{b}$ gives that $$ \frac{\sin \angle M_{c} A X}{\sin \angle M_{b} A X}=\frac{\sin \angle A M_{c} X}{\sin \angle A M_{b} X} \cdot \frac{M_{c} X}{M_{b} X}=\frac{\sin \angle A M_{c} X}{\sin \angle A M_{b} X} \cdot \frac{\sin \angle X M_{a} M_{c}}{\sin \angle X M_{a} M_{b}} . $$ Thus multiplying cyclically gives $$ \prod_{\text {cyc }} \frac{\sin \angle M_{c} A X}{\sin \angle M_{b} A X}=\prod_{\text {cyc }} \frac{\sin \angle A M_{c} X}{\sin \angle A M_{b} X} \prod_{\text {cyc }} \frac{\sin \angle X M_{a} M_{c}}{\sin \angle X M_{a} M_{b}} . $$ The latter product on the right-hand side equals 1 by Trig Ceva on $\triangle M_{a} M_{b} M_{c}$ with cevians $\overline{M_{a} X}, \overline{M_{b} Y}, \overline{M_{c} Z}$. The former product also equals 1 by Trig Ceva for the concurrence in the previous claim (and the fact that $\angle A M_{c} X=\angle H_{c} H_{a} X$ ). Hence the left-hand side equals 1 , implying the result.

|

{

"resource_path": "USA_TST/segmented/en-sols-TST-IMO-2015.jsonl",

"problem_match": null,

"solution_match": null

}

|

2015

|

T0

|

6

| null |

USA_TST

|

Let $A B C$ be a non-equilateral triangle and let $M_{a}, M_{b}, M_{c}$ be the midpoints of the sides $B C, C A, A B$, respectively. Let $S$ be a point lying on the Euler line. Denote by $X, Y, Z$ the second intersections of $M_{a} S, M_{b} S, M_{c} S$ with the nine-point circle. Prove that $A X, B Y, C Z$ are concurrent.

|

We assume now and forever that $A B C$ is scalene since the problem follows by symmetry in the isosceles case. We present four solutions. 『 Third solution by moving points (Gopal Goel). In this solution, we will instead use barycentric coordinates with resect to $\triangle A B C$ to bound the degrees suitably, and then verify for seven distinct choices of $S$. We let $R$ denote the radius of $\triangle A B C$, and $N$ the nine-point center. First, imagine solving for $X$ in the following way. Suppose $\vec{X}=\left(1-t_{a}\right) \vec{M}_{a}+t_{a} \vec{S}$. Then, using the dot product (with $|\vec{v}|^{2}=\vec{v} \cdot \vec{v}$ in general) $$ \begin{aligned} \frac{1}{4} R^{2} & =|\vec{X}-\vec{N}|^{2} \\ & =\left|t_{a}\left(\vec{S}-\vec{M}_{a}\right)+\vec{M}_{a}-\vec{N}\right|^{2} \\ & =\left|t_{a}\left(\vec{S}-\vec{M}_{a}\right)\right|^{2}+2 t_{a}\left(\vec{S}-\vec{M}_{a}\right) \cdot\left(\vec{M}_{a}-\vec{N}\right)+\left|\vec{M}_{a}-\vec{N}\right|^{2} \\ & =t_{a}^{2}\left|\left(\vec{S}-\vec{M}_{a}\right)\right|^{2}+2 t_{a}\left(\vec{S}-\vec{M}_{a}\right) \cdot\left(\vec{M}_{a}-\vec{N}\right)+\frac{1}{4} R^{2} \end{aligned} $$ Since $t_{a} \neq 0$ we may solve to obtain $$ t_{a}=-\frac{2\left(\vec{M}_{a}-\vec{N}\right) \cdot\left(\vec{S}-\vec{M}_{a}\right)}{\left|\vec{S}-\vec{M}_{a}\right|^{2}} $$ Now imagine $S$ varies along the Euler line, meaning there should exist linear functions $\alpha, \beta, \gamma: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ such that $$ S=(\alpha(s), \beta(s), \gamma(s)) \quad s \in \mathbb{R} $$ with $\alpha(s)+\beta(s)+\gamma(s)=1$. Thus $t_{a}=\frac{f_{a}}{g_{a}}=\frac{f_{a}(s)}{g_{a}(s)}$ is the quotient of a linear function $f_{a}(s)$ and a quadratic function $g_{a}(s)$. So we may write: $$ \begin{aligned} X & =\left(1-t_{a}\right)\left(0, \frac{1}{2}, \frac{1}{2}\right)+t_{a}(\alpha, \beta, \gamma) \\ & =\left(t_{a} \alpha, \frac{1}{2}\left(1-t_{a}\right)+t_{a} \beta, \frac{1}{2}\left(1-t_{a}\right)+t_{a} \gamma\right) \end{aligned} $$ $$ =\left(2 f_{a} \alpha: g_{a}-f_{a}+2 f_{a} \beta: g_{a}-f_{a}+2 f_{a} \gamma\right) . $$ Thus the coordinates of $X$ are quadratic polynomials in $s$ when written in this way. In a similar way, the coordinates of $Y$ and $Z$ should be quadratic polynomials in $s$. The Ceva concurrence condition $$ \prod_{\text {cyc }} \frac{g_{a}-f_{a}+2 f_{a} \beta}{g_{a}-f_{a}+2 f_{a} \gamma}=1 $$ is thus a polynomial in $s$ of degree at most six. Our goal is to verify it is identically zero, thus it suffices to check seven positions of $S$. - If $S$ is the circumcenter of $\triangle M_{a} M_{b} M_{c}$ (equivalently the nine-point center of $\triangle A B C$ ) then $\overline{A X}, \overline{B Y}, \overline{C Z}$ are altitudes of $\triangle A B C$. - If $S$ is the centroid of $\triangle M_{a} M_{b} M_{c}$ (equivalently the centroid of $\triangle A B C$ ), then $\overline{A X}$, $\overline{B Y}, \overline{C Z}$ are medians of $\triangle A B C$. - If $S$ is either of the intersections of the Euler line with $\gamma$, then $S=X=Y=Z$ and all cevians concur at $S$. - If $S$ lies on the $\overline{M_{a} M_{b}}$, then $Y=M_{a}, X=M_{c}$, and thus $\overline{A X} \cap \overline{B Y}=C$, which is of course concurrent with $\overline{C Z}$ (regardless of $Z$ ). Similarly if $S$ lies on the other sides of $\triangle M_{a} M_{b} M_{c}$. Thus we are also done.

|

{

"resource_path": "USA_TST/segmented/en-sols-TST-IMO-2015.jsonl",

"problem_match": null,

"solution_match": null

}

|

2015

|

T0

|

6

| null |

USA_TST

|

Let $A B C$ be a non-equilateral triangle and let $M_{a}, M_{b}, M_{c}$ be the midpoints of the sides $B C, C A, A B$, respectively. Let $S$ be a point lying on the Euler line. Denote by $X, Y, Z$ the second intersections of $M_{a} S, M_{b} S, M_{c} S$ with the nine-point circle. Prove that $A X, B Y, C Z$ are concurrent.

|

We assume now and forever that $A B C$ is scalene since the problem follows by symmetry in the isosceles case. We present four solutions. 【 Fourth solution using Pascal (official one). We give a different proof of the claim that $\overline{X H_{a}}, \overline{Y H_{b}}, \overline{Z H_{c}}$ are concurrent (and then proceed as in the end of the second solution). Let $H$ denote the orthocenter, $N$ the nine-point center, and moreover let $N_{a}, N_{b}, N_{c}$ denote the midpoints of $\overline{A H}, \overline{B H}, \overline{C H}$, which also lie on the nine-point circle (and are the antipodes of $M_{a}, M_{b}, M_{c}$ ). - By Pascal's theorem on $M_{b} N_{b} H_{b} M_{c} N_{c} H_{c}$, the point $P=\overline{M_{c} H_{b}} \cap \overline{M_{b} H_{c}}$ is collinear with $N=\overline{M_{b} N_{b}} \cap \overline{M_{c} N_{c}}$, and $H=\overline{N_{b} H_{b}} \cap \overline{N_{c} H_{c}}$. So $P$ lies on the Euler line. - By Pascal's theorem on $M_{b} Y H_{b} M_{c} Z H_{c}$, the point $\overline{Y H_{b}} \cap \overline{Z H_{c}}$ is collinear with $S=\overline{M_{b} Y} \cap \overline{M_{c} Z}$ and $P=\overline{M_{b} H_{c}} \cap \overline{M_{c} H_{b}}$. Hence $Y H_{b}$ and $Z H_{c}$ meet on the Euler line, as needed.

|

{

"resource_path": "USA_TST/segmented/en-sols-TST-IMO-2015.jsonl",

"problem_match": null,

"solution_match": null

}

|

2016

|

T0

|

1

| null |

USA_TST

|

Let $S=\{1, \ldots, n\}$. Given a bijection $f: S \rightarrow S$ an orbit of $f$ is a set of the form $\{x, f(x), f(f(x)), \ldots\}$ for some $x \in S$. We denote by $c(f)$ the number of distinct orbits of $f$. For example, if $n=3$ and $f(1)=2, f(2)=1, f(3)=3$, the two orbits are $\{1,2\}$ and $\{3\}$, hence $c(f)=2$. Given $k$ bijections $f_{1}, \ldots, f_{k}$ from $S$ to itself, prove that $$ c\left(f_{1}\right)+\cdots+c\left(f_{k}\right) \leq n(k-1)+c(f) $$ where $f: S \rightarrow S$ is the composed function $f_{1} \circ \cdots \circ f_{k}$.

|

{

"resource_path": "USA_TST/segmented/en-sols-TST-IMO-2016.jsonl",

"problem_match": null,

"solution_match": null

}

|

|

2016

|

T0

|

2

| null |

USA_TST

|

Let $A B C$ be a scalene triangle with circumcircle $\Omega$, and suppose the incircle of $A B C$ touches $B C$ at $D$. The angle bisector of $\angle A$ meets $B C$ and $\Omega$ at $K$ and $M$. The circumcircle of $\triangle D K M$ intersects the $A$-excircle at $S_{1}, S_{2}$, and $\Omega$ at $T \neq M$. Prove that line $A T$ passes through either $S_{1}$ or $S_{2}$.

|

【 First solution (angle chasing). Assume for simplicity $A B<A C$. Let $E$ be the contact point of the $A$-excircle on $B C$; also let ray $T D$ meet $\Omega$ again at $L$. From the fact that $\angle M T L=\angle M T D=180^{\circ}-\angle M K D$, we can deduce that $\angle M T L=\angle A C M$, meaning that $L$ is the reflection of $A$ across the perpendicular bisector $\ell$ of $B C$. If we reflect $T, D$, $L$ over $\ell$, we deduce $A, E$ and the reflection of $T$ across $\ell$ are collinear, which implies that $\angle B A T=\angle C A E$. Now, consider the reflection point $E$ across line $A I$, say $S$. Since ray $A I$ passes through the $A$-excenter, $S$ lies on the $A$-excircle. Since $\angle B A T=\angle C A E, S$ also lies on ray $A T$. But the circumcircles of triangles $D K M$ and $K M E$ are congruent (from $D M=E M$ ), so $S$ lies on the circumcircle of $\triangle D K M$ too. Hence $S$ is the desired intersection point.

|

{

"resource_path": "USA_TST/segmented/en-sols-TST-IMO-2016.jsonl",

"problem_match": null,

"solution_match": null

}

|

2016

|

T0

|

2

| null |

USA_TST

|

Let $A B C$ be a scalene triangle with circumcircle $\Omega$, and suppose the incircle of $A B C$ touches $B C$ at $D$. The angle bisector of $\angle A$ meets $B C$ and $\Omega$ at $K$ and $M$. The circumcircle of $\triangle D K M$ intersects the $A$-excircle at $S_{1}, S_{2}$, and $\Omega$ at $T \neq M$. Prove that line $A T$ passes through either $S_{1}$ or $S_{2}$.

|

Second solution (advanced). It's known that $T$ is the touch-point of the $A$-mixtilinear incircle. Let $E$ be contact point of $A$-excircle on $B C$. Now the circumcircles of $\triangle D K M$ and $\triangle K M E$ are congruent, since $D M=M E$ and the angles at $K$ are supplementary. Let $S$ be the reflection of $E$ across line $K M$, which by the above the above comment lies on the circumcircle of $\triangle D K M$. Since $K M$ passes through the $A$-excenter, $S$ also lies on the $A$-excircle. But $S$ also lies on line $A T$, since lines $A T$ and $A E$ are isogonal (the mixtilinear cevian is isogonal to the Nagel line). Thus $S$ is the desired intersection point. 【 Authorship comments. This problem comes from an observation of mine: let $A B C$ be a triangle, let the $\angle A$ bisector meet $\overline{B C}$ and $(A B C)$ at $E$ and $M$. Let $W$ be the tangency point of the $A$-mixtilinear excircle with the circumcircle of $A B C$. Then $A$ Nagel line passed through a common intersection of the circumcircle of $\triangle M E W$ and the $A$-mixtilinear incircle. This problem is the inverted version of this observation.

|

{

"resource_path": "USA_TST/segmented/en-sols-TST-IMO-2016.jsonl",

"problem_match": null,

"solution_match": null

}

|

2016

|

T0

|

3

| null |

USA_TST

|

Let $p$ be a prime number. Let $\mathbb{F}_{p}$ denote the integers modulo $p$, and let $\mathbb{F}_{p}[x]$ be the set of polynomials with coefficients in $\mathbb{F}_{p}$. Define $\Psi: \mathbb{F}_{p}[x] \rightarrow \mathbb{F}_{p}[x]$ by $$ \Psi\left(\sum_{i=0}^{n} a_{i} x^{i}\right)=\sum_{i=0}^{n} a_{i} x^{x^{i}} . $$ Prove that for nonzero polynomials $F, G \in \mathbb{F}_{p}[x]$, $$ \Psi(\operatorname{gcd}(F, G))=\operatorname{gcd}(\Psi(F), \Psi(G)) $$

|

Observe that $\Psi$ is also a linear map of $\mathbb{F}_{p}$ vector spaces, and that $\Psi(x P)=\Psi(P)^{p}$ for any $P \in \mathbb{F}_{p}[x]$. (In particular, $\Psi(1)=x$, not 1 , take caution!) 『 First solution (Ankan Bhattacharya). We start with: Claim - If $P \mid Q$ then $\Psi(P) \mid \Psi(Q)$. $$ \Psi(Q)=\Psi\left(P \sum_{i=0}^{k} r_{i} x^{i}\right)=\sum_{i=0}^{k} \Psi\left(P \cdot r_{i} x^{i}\right)=\sum_{i=0}^{k} r_{i} \Psi(P)^{p^{i}} $$ which is divisible by $\Psi(P)$. This already implies $$ \Psi(\operatorname{gcd}(F, G)) \mid \operatorname{gcd}(\Psi(F), \Psi(G)) $$ For the converse, by Bezout there exists $A, B \in \mathbb{F}_{p}[x]$ such that $A F+B G=\operatorname{gcd}(F, G)$, so taking $\Psi$ of both sides gives $$ \Psi(A F)+\Psi(B G)=\Psi(\operatorname{gcd}(F, G)) $$ The left-hand side is divisible by $\operatorname{gcd}(\Psi(F), \Psi(G))$ since the first term is divisible by $\Psi(F)$ and the second term is divisible by $\Psi(G)$. So $\operatorname{gcd}(\Psi(F), \Psi(G)) \mid \Psi(\operatorname{gcd}(F, G))$ and noting both sides are monic we are done.

|

{

"resource_path": "USA_TST/segmented/en-sols-TST-IMO-2016.jsonl",

"problem_match": null,

"solution_match": null

}

|

2016

|

T0

|

3

| null |

USA_TST

|

Let $p$ be a prime number. Let $\mathbb{F}_{p}$ denote the integers modulo $p$, and let $\mathbb{F}_{p}[x]$ be the set of polynomials with coefficients in $\mathbb{F}_{p}$. Define $\Psi: \mathbb{F}_{p}[x] \rightarrow \mathbb{F}_{p}[x]$ by $$ \Psi\left(\sum_{i=0}^{n} a_{i} x^{i}\right)=\sum_{i=0}^{n} a_{i} x^{x^{i}} . $$ Prove that for nonzero polynomials $F, G \in \mathbb{F}_{p}[x]$, $$ \Psi(\operatorname{gcd}(F, G))=\operatorname{gcd}(\Psi(F), \Psi(G)) $$

|

Observe that $\Psi$ is also a linear map of $\mathbb{F}_{p}$ vector spaces, and that $\Psi(x P)=\Psi(P)^{p}$ for any $P \in \mathbb{F}_{p}[x]$. (In particular, $\Psi(1)=x$, not 1 , take caution!) 【 Second solution. Here is an alternative (longer but more conceptual) way to finish without Bezout lemma. Let $\beth \subseteq \mathbb{F}_{p}[x]$ denote the set of polynomials in the image of $\Psi$, thus $\Psi: \mathbb{F}_{p}[x] \rightarrow \beth$ is a bijection on the level of sets. Claim - If $A, B \in \beth$ then $\operatorname{gcd}(A, B) \in \beth$. $$ \begin{aligned} x^{p^{k}} & \equiv\left(c_{2} x^{p^{k-2}}+c_{3} x^{p^{k-3}}+\cdots+c_{k}\right)^{p} \quad(\bmod B) \\ & \equiv c_{2} x^{p^{k-1}}+c_{3} x^{p^{k-2}} \cdots+c_{k} \quad(\bmod B) \end{aligned} $$ since exponentiation by $p$ commutes with addition in $\mathbb{F}_{p}$. This is enough to imply the conclusion. The proof if $\operatorname{deg} B$ is smaller less than $p^{k-1}$ is similar. Thus, if we view $\mathbb{F}_{p}[x]$ and $\beth$ as partially ordered sets under polynomial division, then gcd is the "greatest lower bound" or "meet" in both partially ordered sets. We will now prove that $\Psi$ is an isomorphism of the posets. We have already seen that $P|Q \Longrightarrow \Psi(P)| \Psi(Q)$ from the first solution. For the converse: Claim - If $\Psi(P) \mid \Psi(Q)$ then $P \mid Q$. Remark. In fact $\Psi: \mathbb{F}_{p}[x] \rightarrow \beth$ is a ring isomorphism if we equip $\beth$ with function composition as the ring multiplication. Indeed in the proof of the first claim (that $P|Q \Longrightarrow \Psi(P)|$ $\Psi(Q)$ ) we saw that $$ \Psi(R P)=\sum_{i=0}^{k} r_{i} \Psi(P)^{p^{i}}=\Psi(R) \circ \Psi(P) $$

|

{

"resource_path": "USA_TST/segmented/en-sols-TST-IMO-2016.jsonl",

"problem_match": null,

"solution_match": null

}

|

2016

|

T0

|

4

| null |

USA_TST

|

Let $\sqrt{3}=1 . b_{1} b_{2} b_{3} \cdots(2)$ be the binary representation of $\sqrt{3}$. Prove that for any positive integer $n$, at least one of the digits $b_{n}, b_{n+1}, \ldots, b_{2 n}$ equals 1 .

|

Assume the contrary, so that for some integer $k$ we have $$ k<2^{n-1} \sqrt{3}<k+\frac{1}{2^{n+1}} . $$ Squaring gives $$ \begin{aligned} k^{2}<3 \cdot 2^{2 n-2} & <k^{2}+\frac{k}{2^{n}}+\frac{1}{2^{2 n+2}} \\ & \leq k^{2}+\frac{2^{n-1} \sqrt{3}}{2^{n}}+\frac{1}{2^{2 n+2}} \\ & =k^{2}+\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}+\frac{1}{2^{2 n+2}} \\ & \leq k^{2}+\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}+\frac{1}{16} \\ & <k^{2}+1 \end{aligned} $$ and this is a contradiction.

|

{

"resource_path": "USA_TST/segmented/en-sols-TST-IMO-2016.jsonl",

"problem_match": null,

"solution_match": null

}

|

2016

|

T0

|

5

| null |

USA_TST

|

Let $n \geq 4$ be an integer. Find all functions $W:\{1, \ldots, n\}^{2} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ such that for every partition $[n]=A \cup B \cup C$ into disjoint sets, $$ \sum_{a \in A} \sum_{b \in B} \sum_{c \in C} W(a, b) W(b, c)=|A||B||C| . $$

|

$ Of course, $W(k, k)$ is arbitrary for $k \in[n]$. We claim that $W(a, b)= \pm 1$ for any $a \neq b$, with the sign fixed. (These evidently work.) First, let $X_{a b c}=W(a, b) W(b, c)$ for all distinct $a, b, c$, so the given condition is $$ \sum_{a, b, c \in A \times B \times C} X_{a b c}=|A||B||C| . $$ Consider the given equation with the particular choices - $A=\{1\}, B=\{2\}, C=\{3,4, \ldots, n\}$. - $A=\{1\}, B=\{3\}, C=\{2,4, \ldots, n\}$. - $A=\{1\}, B=\{2,3\}, C=\{4, \ldots, n\}$. This gives $$ \begin{aligned} X_{123}+X_{124}+\cdots+X_{12 n} & =n-2 \\ X_{132}+X_{134}+\cdots+X_{13 n} & =n-2 \\ \left(X_{124}+\cdots+X_{12 n}\right)+\left(X_{134}+\cdots+X_{13 n}\right) & =2(n-3) . \end{aligned} $$ Adding the first two and subtracting the last one gives $X_{123}+X_{132}=2$. Similarly, $X_{123}+X_{321}=2$, and in this way we have $X_{321}=X_{132}$. Thus $W(3,2) W(2,1)=$ $W(1,3) W(3,2)$, and since $W(3,2) \neq 0$ (clearly) we get $W(2,1)=W(3,2)$. Analogously, for any distinct $a, b, c$ we have $W(a, b)=W(b, c)$. For $n \geq 4$ this is enough to imply $W(a, b)= \pm 1$ for $a \neq b$ where the choice of sign is the same for all $a$ and $b$. Remark. Surprisingly, the $n=3$ case has "extra" solutions for $W(1,2)=W(2,3)=$ $W(3,1)= \pm 1, W(2,1)=W(3,2)=W(1,3)=\mp 1$. Remark (Intuition). It should still be possible to solve the problem with $X_{a b c}$ in place of $W(a, b) W(b, c)$, because we have about far more equations than variables $X_{a, b, c}$ so linear algebra assures us we almost certainly have a unique solution.

|

{

"resource_path": "USA_TST/segmented/en-sols-TST-IMO-2016.jsonl",

"problem_match": null,

"solution_match": null

}

|

2016

|

T0

|

6

| null |

USA_TST

|

Let $A B C$ be an acute scalene triangle and let $P$ be a point in its interior. Let $A_{1}$, $B_{1}, C_{1}$ be projections of $P$ onto triangle sides $B C, C A, A B$, respectively. Find the locus of points $P$ such that $A A_{1}, B B_{1}, C C_{1}$ are concurrent and $\angle P A B+\angle P B C+$ $\angle P C A=90^{\circ}$.

|

In complex numbers with $A B C$ the unit circle, it is equivalent to solving the following two cubic equations in $p$ and $q=\bar{p}$ : $$ \begin{aligned} (p-a)(p-b)(p-c) & =(a b c)^{2}(q-1 / a)(q-1 / b)(q-1 / c) \\ 0 & =\prod_{\text {cyc }}(p+c-b-b c q)+\prod_{\text {сус }}(p+b-c-b c q) \end{aligned} $$ Viewing this as two cubic curves in $(p, q) \in \mathbb{C}^{2}$, by Bézout's Theorem it follows there are at most nine solutions (unless both curves are not irreducible, but it's easy to check the first one cannot be factored). Moreover it is easy to name nine solutions (for $A B C$ scalene): the three vertices, the three excenters, and $I, O, H$. Hence the answer is just those three triangle centers $I, O$ and $H$. Remark. On the other hand it is not easy to solve the cubics by hand; I tried for an hour without success. So I think this solution is only feasible with knowledge of algebraic geometry. Remark. These two cubics have names: - The locus of $\angle P A B+\angle P B C+\angle P C A=90^{\circ}$ is the McCay cubic, which is the locus of points $P$ for which $P, P^{*}, O$ are collinear. - The locus of the pedal condition is the Darboux cubic, which is the locus of points $P$ for which $P, P^{*}, L$ are collinear, $L$ denoting the de Longchamps point. Assuming $P \neq P^{*}$, this implies $P$ and $P^{*}$ both lie on the Euler line of $\triangle A B C$, which is possible only if $P=O$ or $P=H$.

|

{

"resource_path": "USA_TST/segmented/en-sols-TST-IMO-2016.jsonl",

"problem_match": null,

"solution_match": null

}

|

2017

|

T0

|

1

| null |

USA_TST

|

In a sports league, each team uses a set of at most $t$ signature colors. A set $S$ of teams is color-identifiable if one can assign each team in $S$ one of their signature colors, such that no team in $S$ is assigned any signature color of a different team in $S$. For all positive integers $n$ and $t$, determine the maximum integer $g(n, t)$ such that: In any sports league with exactly $n$ distinct colors present over all teams, one can always find a color-identifiable set of size at least $g(n, t)$.

|

Answer: $\lceil n / t\rceil$. To see this is an upper bound, note that one can easily construct a sports league with that many teams anyways. A quick warning: Remark (Misreading the problem). It is common to misread the problem by ignoring the word "any". Here is an illustration. Suppose we have two teams, MIT and Harvard; the colors of MIT are red/grey/black, and the colors of Harvard are red/white. (Thus $n=4$ and $t=3$.) The assignment of MIT to grey and Harvard to red is not acceptable because red is a signature color of MIT, even though not the one assigned. 【 Approach by deleting teams (Gopal Goel). Initially, place all teams in a set $S$. Then we repeat the following algorithm: If there is a team all of whose signature colors are shared by some other team in $S$ already, then we delete that team. (If there is more than one such team, we pick arbitrarily.) At the end of the process, all $n$ colors are still present at least once, so at least $\lceil n / t\rceil$ teams remain. Moreover, since the algorithm is no longer possible, the remaining set $S$ is already color-identifiable. Remark (Gopal Goel). It might seem counter-intuitive that we are deleting teams from the full set when the original problem is trying to get a large set $S$. This is less strange when one thinks of it instead as "safely deleting useless teams". Basically, if one deletes such a team, the problem statement implies that the task must still be possible, since $g(n, t)$ does not depend on the number of teams: $n$ is the number of colors present, and deleting a useless team does not change this. It turns out that this optimization is already enough to solve the problem.

|

{

"resource_path": "USA_TST/segmented/en-sols-TST-IMO-2017.jsonl",

"problem_match": null,

"solution_match": null

}

|

2017

|

T0

|

1

| null |

USA_TST

|

In a sports league, each team uses a set of at most $t$ signature colors. A set $S$ of teams is color-identifiable if one can assign each team in $S$ one of their signature colors, such that no team in $S$ is assigned any signature color of a different team in $S$. For all positive integers $n$ and $t$, determine the maximum integer $g(n, t)$ such that: In any sports league with exactly $n$ distinct colors present over all teams, one can always find a color-identifiable set of size at least $g(n, t)$.

|